As Pirates prospect Matt Benedict tossed a baseball on Roberto Clemente Field at Pittsburgh's minor league complex late one Sunday afternoon, five blue sensors attached to his body recorded 39 sets of measurements ranging from shoulder rotation to hip speed to stride.

Minutes later, the 27-year-old right-hander examined a hand-held computer, checking how he rated against test groups.

Biometric baseball has arrived.

Programmers already have revolutionized the game with defensive shifts. Now they hope for a new level of diamond data that will stop the spate of torn ulnar collateral ligaments in elbows and an epidemic of Tommy John surgeries.

"It's the next sabermetrics," said Glenn Fleisig, a Ph.D. in biomedical engineering who directs research at Dr. James Andrews' American Sports Medicine Institute.

"It's science and the competitive advantage of knowing what your players are doing vs. other people not knowing what their players are doing," he said.

For the scientists, Newton meters is the next big baseball stat, measuring valgus torque — stress on the elbow.

Motus Global, a company founded in 2010 by creators of the motion capture software for the Grand Theft Auto III and IV video games, is launching its five-sensor MotusPro system this year and a single-sensor sleeve for consumers with a $150 price tag.

While the company says 27 of the 30 big league teams have used its products, some players worry wearable technology might turn against them — kind of like a malevolent HAL 9000 in "2001: A Space Odyssey" — and provide management with damaging data.

In-game use for the major and minor leagues isn't allowed for this year, and players can decide on their own whether to use during workouts.

"The union, without some negotiation, would never let the teams have that information," said Toronto pitcher R.A. Dickey, a former NL Cy Young Award winner, "because they would use it in arbitration, they'd use it in contract negotiations. I would, too, if I was an owner or a team."

Based in the New York City suburb of Massapequa and with a lab at the IMG Academy in Bradenton, Motus was launched in 2010 by Joe Nolan and Keith Robinson. They both attended the New York Institute of Technology and founded Perspective Studios, where they worked with Electronic Arts, MTV Games, Sony Computer Entertainment, Microsoft Game Studio and others.

They sold Perspective in 2009 to Rockstar Games, a division of Take-Two Interactive Software Inc., and thought about another venture.

"We just looked for an area where we thought there was a real growth opportunity and we could sort of deploy our experience in movement analysis," Nolan said.

ASMI has been measuring pitchers' biomechanics since 1990, but players had to go to a lab in Birmingham, Alabama, strip to their shorts and attach 30-50 reflective markers. With advancements, Motus developed a 16-millimeter, 14-ounce sensor that was tested last year. This year's model is down to 9 millimeters and 7 ounces.

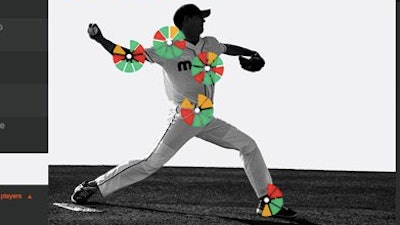

The top-of-the-line system includes two chips on a compression sleeve that slides over a pitcher's arm: a master sensor with a blue dot over the elbow and another with a red dot over the biceps. A detector with a green dot slides into a pocket over the chest and one with a yellow dot over the belly button. The final sensor, with a purple dot, is affixed to the pitcher's lead foot. Bluetooth technology can transmit the details a throw within 9 seconds, or the stats can be downloaded after a bullpen, inning or game.

Benedict resembled The Six Million Dollar Man more than the pitch-till-your-arm-hurt prototype that dominated the sport for a century.

"I'm not a huge physics guy. But from the way they can break it down and help you understand exactly what's going on with your body, I think it would be something that most people would be able to learn," said Benedict, a 30th-round draft pick in 2011 who made it up to Triple-A last year.

"For someone who is maybe rehabbing and wants to see where they're at in their progression, it could be a great tool for them."

To establish models, Motus evaluated 750 pitchers who threw over 90 mph and at the time of testing had not sustained an injury during the previous two years.

"One of the major goals of our single-sensor system is to measure workload on the UCL, the Tommy John ligament, and that's meant to be worn every day, the moment a player steps on the field till the moment they step off," said Ben Hansen, Motus' chief technology officer.

"What we're seeing now is we have 18 months of what a Major League Baseball pitcher's throwing regimen looks like, and it's fascinating to see this data," he added. "We hope players continue to wear it and we see what their workloads are throughout a career and what workloads lead to injury. That's our ultimate goal."

New York Mets medical director Dr. David Altchek, who like Fleisig is a Motus consultant, said several years of data will be needed before judgments can be made on how much elbow stress is too much. He sees three immediate purposes for the Newton meters measurement: comparing throwing off a mound with tossing on flat ground, monitoring exertion during rehabilitation and "for kids to keep the Newton meters down when their growth plates are open."

After watching a demonstration of the 2015 model, New York Yankees pitching coach Larry Rothschild was skeptical. He didn't think the sensor was that stable on the elbow, an issue Motus says the smaller chip has done away with.

"It's got a ways to go," Rothschild said. "Unless the guy's in a game and cranking it up, I'm not sure what information you're getting. And a lot of players aren't going to wear this."

Altchek doesn't envision pitchers wearing sensors on the mound in contests that count — "the likelihood of using that in games is like the likelihood of the PGA Tour allowing players to use range finders." But Yankees reliever Andrew Miller, who played college ball with Hansen at North Carolina, says miniaturization may eventually change that, assuming privacy concerns are addressed.

"Who knows? In 10 years, they may be so small and unnoticeable and guys are so used to them, every single person in the big leagues is wearing them in an important game," Miller said. "They might be worn in World Series games."