TOLEDO, OH (AP) — Nearly four weeks into the United Auto Workers' strike against General Motors, employees are starting to feel the pinch of going without their regular paychecks.

They're scaling back at the grocery, giving up on eating at restaurants and some are taking on part-time jobs while trying to get by on weekly strike pay of $250.

"In a couple of more weeks, I think everybody's going to be calling the bank or their creditors, going, 'Hey, probably going to be late or delinquent,'" said Mike Armentrout, who works at GM's transmission plant in Toledo.

While pressure is intensifying to reach a deal, the losses for both sides are mounting and spilling over into the auto supply chain.

Striking full-time workers are losing roughly $1,000 each week, and that's not counting the overtime many of them make.

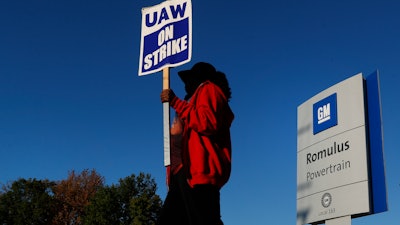

Dolphin Green, a temporary worker at an engine and transmission plant in the Detroit suburb of Romulus, Michigan, took a job washing dishes at a restaurant to help make ends meet.

"I'm willing to sacrifice as long as possible," he said.

He's only been with GM for four months, making just under $16 per hour, but has hopes of going full-time so he can support a family.

Use of temporary workers has been a major issue in the contract negotiations, along with building vehicles in other countries, a point that surfaced on Tuesday.

Green has cut spending and has a girlfriend with a good job. But he's worried about a child support payment coming up at the end of the month and has talked to his case worker about temporarily reducing the payments.

Dennis Earl, president of UAW Local 14 in Toledo, said the union is doing what it can to help workers by advising them how to deal with bills that are piling up.

The union hall's kitchen is serving meals around the clock and donations of food and household items are pouring in from other labor groups in the area. "Nobody's going to go hungry," he said.

"As this goes on and becomes more difficult, there's going to be some agitation, but for the most part these people are in it for the long haul," he said.

A Wall Street analyst estimates that GM has lost over $1.6 billion since the work stoppage began, and is now losing about $82 million per day.

GM dealers across the country report still-healthy inventory on their lots, but they're running short of parts to fix their customers' vehicles.

The strike immediately shut down about 30 GM factories across the U.S., essentially ending the company's production. Factories in Canada and Mexico remained open for a while, but one assembly plant in Canada and another in Mexico have been forced to shut down due to parts shortages. Analysts expect the closures to spread to the six plants that remain open.

Bargaining went into the night Wednesday and resumed Thursday morning as the strike entered its 25th day.

A person briefed on the talks said the union hasn't responded to an improved offer the company made on Monday. The person didn't want to be identified because the talks are confidential. The union pointed to a letter from its top bargainer to members saying that GM isn't committed to bringing production to the U.S. from other countries.

Many workers stocked away emergency cash after being warned for months by union leaders about the possibility of a strike, but they said GM's temporary workers who make much less couldn't do that.

"We all knew this was coming for a long time, I'm set up. A lot of guys aren't in that same spot," said Tim Leiby, an eight-year employee in Toledo. "I've got all my bills paid, but I know some people who don't."

Still, he's cutting back on eating out, going to the movies and spending money on hobbies because "we don't know how long this will last."

He also said he has a cousin who won't talk to him now because the strike has shut down the welding shop where she works.

"It's affecting everybody, it's affecting families. Even families that don't work here," he said.

The Anderson Economic Group, a consulting firm in East Lansing, Michigan, estimates that 75,000 workers at auto parts supply companies have been laid off or had their wages reduced because of the strike.

That doesn't include waitresses, convenience store clerks and others who are seeing their hours cut because striking workers aren't out spending money.

Truck driver Glen Hodge, who hauls scrap metal from a stamping plant in Spring Hill, Tennessee, has been off the job the past three weeks.

Since then, he's filed for unemployment, dropped his cable TV package, stopped going out to eat with his wife and even cut back on dog treats. It upsets him a bit when he sees gift cards and donations pouring in for the striking workers.

"What about the rest of us?" he said on Wednesday. "There's a bunch of us sitting around getting nothing."