WASHINGTON (AP) — Just last week, solid economic numbers appeared to be helping President Donald Trump's reelection prospects.

The United States had achieved its longest economic expansion. Stock prices were climbing. Job gains were steady. Consumers had scaled up spending. Growth was sturdy enough to presage a second term for a conventional president, according to election forecasts based on the economy.

But Trump was not content to play it safe.

He chose to magnify the trade war with China and almost instantly destabilized the economy in ways that could hurt his 2020 chances if the conflict persists. Stocks tanked in response to his planned 10 percent tax on $300 billion of Chinese imports. Retailers warned of price hikes. The value of the Chinese currency fell and the spillovers from that could weaken U.S. growth. For the first time after six days of sell-offs, investors on Tuesday were catching their breath to consider the uncertain path ahead from an inflamed trade war between the world's two largest economies.

Part of the challenge is that the president's penchant for uncertainty — the opposite of what investors seek — makes it difficult to know just how much risk Trump is taking with an election 16 months from now. But what is clear is that the range of possible outcomes for the economy is greater than they were a week ago. "The more that you deepen or broaden this conflict, the greater the risk of misunderstandings, miscalculations and unintended consequences," said Mike Ryan, chief investment officer at Americas for UBS Global Wealth Management.

Among the many possibilities: Trump might be able to strong-arm China into a trade agreement that favors the United States; he might suffer politically if the tariffs hurt U.S. farmers, manufacturers and consumers; he might agree to a cursory deal and hope to ride a stock market rally to reelection; or, he could be setting up a global recession that could eventually engulf the United States.

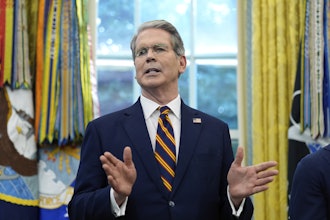

Larry Kudlow, director of the White House National Economic Council, provided little clarity Tuesday about the new tariffs that are to be implemented September 1. The Trump administration already has a 25 percent tax on $250 billion worth of Chinese imports in addition to the upcoming tariffs. Kudlow told CNBC the tariffs "might get worse" if the trade talks scheduled for next month flounder or they might be delayed if progress is achieved.

The president's chief economic adviser acknowledged that China might simply try to endure the tariffs on the hopes that Trump loses in 2020 and the taxes are lifted by his Democratic successor. "China can wait, that's up to them," Kudlow said. "But I think they will continue to do great damage to their economy. The American economy is very strong. Theirs is not."

Increasingly, the administration's actions on China are driven by the president himself, with Trump taking more control of the direction of the negotiations and retaliations.

Trump, aides and advisers said, is caught between a desire to maintain the appearance of toughness toward China and the political and economic realities of an elongated trade war. While the president says that the Chinese economy is paying a steeper price than the United States, he is acutely aware of the political risks of a downturn.

In recent weeks Trump has adopted a two-pronged message. He is insisting that China badly wants a deal, but he also is the one holding out for more on behalf of the American people, and he is claiming China is looking to wait-out his administration so he'll keep increasing pressure. White House aides suggested that the diametrically opposite arguments reflected the twin audiences of the president's public statements, namely Chinese negotiators and his political base.

The reality, they said, is somewhere in the middle, with the president looking to find the quickest off-ramp from the trade war that doesn't allow him to be portrayed as weak — competing priorities that may not be reconcilable in the short term. Nor is the situation under Trump's control because China could easily retaliate and apply direct pressure on U.S. companies.

Beijing has already responded by increasing import duties on $110 billion of U.S. goods. But regulators can delay customs clearances and delay government-required licensing, as well as create an "unreliable entities" blacklist of U.S. businesses.

Nearly half of Americans, 47 percent, approve of how Trump has handled the economy, according to a June survey by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. But tariffs, in particular, are a weakness for the president.

Only 15 percent of those surveyed said the import taxes launched by Trump would personally help them. Just 19 percent believed tariffs would help their local community, and 26 percent said the tariffs would aid the entire U.S. economy, down from 40 percent in August 2018. The survey shows that Republicans are becoming skeptical that the president's tariffs will improve the economy.

Farmers have especially felt the brunt from the tariffs, as China has targeted U.S. agricultural exports as retaliation. Dave Daniels, a dairy farmer in Wisconsin who voted for the president in 2016, said the Trump administration has helped by offsetting the cost of lost exports to China. But he said it was "a little disappointing" that the president chose to escalate.

"As long as they can keep talking I guess I am, I'm happy about that, but we'll see what happens in the next few months," he said.

Election models based on the economy are bullish on Trump's reelection. These models do not necessarily account for the president's personality or his willingness to campaign on divisive cultural issues such as immigration, abortion and race.

Yale University professor Ray Fair found that Democrats would only get 46.2 percent of the presidential vote based primarily on current economic conditions, down from the 48.2 percent that Democrat Hillary Clinton received in 2016.

An economic model developed by investor Donald Luskin suggests that Trump would receive 340 electoral votes, significantly more than the 270 needed to win the presidency. But he cautioned that the new tariffs presented an "unlikely but credible nightmare scenario" in which China spiraled into a recession. That could then lead to a downturn in the United States and erode the president's relative strength on the economy.

"It's not that we can't take China down," Luskin said. "It's that we can't take China down without taking ourselves down."