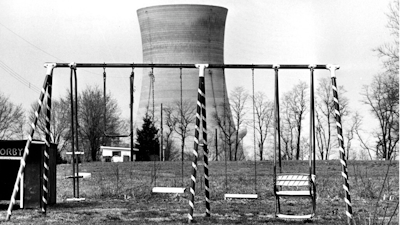

HARRISBURG, Pa. (AP) — Four decades after Three Mile Island became shorthand for America's worst commercial nuclear power accident, financial rescues of nuclear power plants are stirring the highest levels of government.

In Pennsylvania, nuclear power plant owners have been working for two years to build support for the kind of financial packages already approved by New York, New Jersey and Illinois. Meanwhile, those packages have sparked legal appeals to the U.S. Supreme Court and a debate among federal energy regulators over protecting ratepayers from higher electricity prices.

Those loose ends are shadowing Pennsylvania as state lawmakers prepare to decide whether to help their state's nuclear power plants.

"Anything that Pennsylvania does is going to be subject to a degree of policy and legal uncertainty," said Christina Simeone, director of policy and external affairs at the Kleinman Center for Energy Policy at the University of Pennsylvania.

The nation's aging and shrinking nuclear power fleet is being buffeted by a flood of natural gas plants entering competitive electricity markets, relatively flat post-recession electricity demand, and states putting more emphasis on renewable energy and efficiency.

The pursuit of state guarantees has spurred questions over why ratepayers should foot the cost to keep nuclear power plants open, and whether nuclear power provides an indispensable environmental benefit in the age of global warming.

The spotlight moved in 2017 to Pennsylvania, the nation's No. 2 nuclear power state.

That's when Three Mile Island's owner, Chicago-based Exelon Corp., announced it will close the plant that was the site of a terrifying partial meltdown in 1979 unless Pennsylvania comes to its financial rescue. It set this Sept. 30 as the closing date.

Ohio-based FirstEnergy Corp. also said it will shut down its Beaver Valley nuclear power plant in western Pennsylvania — as well as two nuclear plants in Ohio — within three years unless Pennsylvania steps up.

So far, no rescue has been written into legislation.

Rather, sympathetic lawmakers have issued a broadly worded memo saying they will introduce legislation to effectively give Pennsylvania's nuclear power plants the same preferential treatment as solar power, wind power and a handful of other niche energy sources received under a 2004 state law.

The owners of Pennsylvania's five nuclear power plants — primarily Exelon, FirstEnergy and Allentown-based Talen Energy — are backing that effort.

PJM Interconnection, which operates the electric grid covering Pennsylvania and the 65 million people from Illinois east to Washington, has said those four nuclear power plant closings — two in Pennsylvania and two in Ohio — won't affect the availability of electricity.

But, last summer, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, in a 3-2 decision, ordered PJM to come up with a solution to protect the competitive market from what it described as a dangerous cascade of pressure on states to prop up otherwise viable power plants.

PJM pitched an idea in October that, if adopted, could create new dilemmas, particularly for nuclear power plant owners.

"At that point, do they come back to the state and ask for more? Maybe," said Glen Thomas, a Pennsylvania-based consultant who specializes in utility regulations. "Do they go out of business because they don't have enough revenue? Maybe. Does it suppress the market price for other generators? Definitely. It creates some problems for sure."

It's a long-shot that the U.S. Supreme Court will take up appeals in lawsuits challenging New York's and Illinois' nuclear power subsidies, say lawyers following the cases.

But FERC action still looms, and it's not clear when or how commissioners will respond.

Exelon said Pennsylvania must enact legislation by June 1 if it is to keep operating Three Mile Island, since fuel must be ordered months in advance.

Gov. Tom Wolf hasn't taken a position on rescuing Pennsylvania's nuclear power plants — although his administration suggests that keeping them operating would help slash Pennsylvania's greenhouse gas emissions over the coming decades — and neither have top lawmakers.

Meanwhile, the fight is sweeping up labor unions, business associations, ratepayer advocates, the AARP, environmental groups, anti-nuclear power activists and Pennsylvania's considerable natural gas industry.

"FERC has created all this uncertainty," said Miles Farmer, an attorney for the Washington, D.C.-based Natural Resources Defense Council. "It's not clear how customers are going to be protected and it's very difficult for states to set up their programs when they're in the dark as to how the rules will work."