The tiny balloon was supposed to stretch open a blocked artery on Charles Riegel's diseased heart. Instead, when the doctor inflated the balloon, it burst.

The patient went on life support but survived. His lawsuit against the manufacturer of that arterial balloon did not.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of Medtronic, among the world's largest makers of medical devices, setting a precedent that has killed lawsuits involving some of the most sophisticated devices on the market.

___

WHAT DID THE SUPREME COURT DECISION DO?

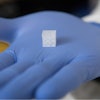

The device that harmed Riegel had cleared the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's most rigorous review, known as "pre-market approval." To reach consumers, Medtronic provided regulators with documentation that the Evergreen Balloon Catheter would be safe and effective.

In Riegel v. Medtronic Inc., the justices grappled with whether Medtronic had any liability. They ruled that devices that have received pre-market approval are effectively immune from product liability lawsuits in state courts, where juries can award huge sums. The reasoning: Congress wrote that states couldn't add safety requirements beyond what the FDA imposes.

Since the Supreme Court ruling in 2008, rare is the case when a manufacturer must pay suffering, lost wages and other compensation to patients who claim they were injured by a pre-market approved device. Patients who believe they've been harmed can still sue device makers in federal court.

___

WHY IS THIS LEGAL PRECEDENT GOOD PUBLIC POLICY?

Because manufacturers can produce new devices without worrying about big lawsuits.

"There's a huge social benefit to encouraging medical technology innovation," said Joe Winebrenner, a Minnesota attorney who has represented medical device companies. "It saves lives, it lengthens lives, it improves lives."

___

WHY IS THE PRECEDENT BAD PUBLIC POLICY?

Because manufacturers can produce new devices without worrying about big lawsuits.

Legal exposure is a powerful incentive to maximize safety, noted Dr. Hooman Noorchashm, a heart surgeon who stopped practicing to form a patient-advocacy group. Noorchashm criticized the Supreme Court precedent as fundamentally flawed, saying it places too much faith in the FDA's pre-market review.

"That's just a deadly assumption," he said, "because there's no such thing as perfection."

___

WHO'S GETTING SHUT OUT?

People like George Davis, who runs a small furniture company in Pensacola, Florida, with his wife, Brenda.

To help relieve chronic back pain, Davis was implanted in 2016 with a spinal-cord stimulator made by Boston Scientific, another major manufacturer.

The devices are supposed to interrupt pain signals before they reach the brain, but the battery in Davis' device would overheat and burn his skin. Sharp pains would shoot up and down his spine, he said, and a massive infection broke out at the surgical site.

Doctors removed the device, but not before debilitating damage had been done, Davis said. He wanted to sue, but lawyers declined to take on his case, citing the Supreme Court ruling.

"The attorneys said it would cost too much money, the companies were too big, and they didn't think we'd win," Brenda Simpson-Davis said. "That case has had a chilling effect."