MALMO, Sweden (AP) — Something high-tech is happening in the produce aisle at some Swedish supermarkets, where laser marks have replaced labels on the organic avocados and sweet potatoes.

Swedish supermarket chain ICA started experimenting in December with "natural branding," a process that uses low-energy carbon dioxide lasers to remove the pigment from the outer skins of fruits and vegetables.

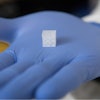

The laser beams create tattoo-like patterns — in this case the product's name, country of origin and code number — similar to the way hot irons brand cattle. If its test is successful, ICA, which has 1,350 stores across Sweden, hopes to cut down on the stickers and packaging it now uses to identify its organic produce.

"It's a new technique, and we are searching for a smarter way of branding our products due to the fact that we think we have too much unnecessary plastic material or packaging material on our products," Peter Hagg, the chain's senior manager for fruits and vegetables, said.

ICA decided to start with sweet potatoes and avocados because their peels are not typically eaten and have a tendency to shed the stickers normally used to brand produce. But branded broccoli and engraved eggplants may not be far behind.

Later this year, the chain plans to test laser-marking melons plus some items with consumable skins to gauge consumer reaction. Hagg claims lasering has no negative effects on the fruit and vegetables.

"It's very delicate. Because the mark is not going through the skin in any way, it doesn't affect the quality or taste of the product," he said.

Jonas Kullendorff, a 29-year-old engineer, says he approves of the method, if it reduces packaging waste.

"It's actually the first time I've seen this branding, but if it's (a) more sustainable alternative, I'm all for it," Kullendorff said. "No, I wouldn't say it would put me off. If it's less packaging materials, that's a good thing."

Laser labeling has been used in Australia and New Zealand since 2009 and was approved for use in European Union countries in 2013, according to Eosta, the Netherlands-based produce supplier that is working with ICA to test the technology in Sweden.

Eosta says it sold over 725,000 packs of organically grown avocados to the supermarket chain in 2015. Packing them required about 220 kilometers (135 miles) of plastic wrap. The avocados etched by Eosta now sit in open bins without stickers or packaging.

Laser marking can't be used on all produce. Citrus fruit, for example, has the ability to heal itself, meaning the etchings would disappear after just a few hours. Packaging still is desirable in some cases to extend a product's shelf life, Hagg said.

"The plastic branding — there is of course positive things with it," he said. "But in some items it's just unnecessary, because it doesn't bring you better shelf life. It just brings you extra costs."

Central to the trial's success will be consumer response and whether shoppers are happy to eat something that's been zapped by a laser.

"It's really new to me, but I think it's a really good idea (for) the environment," Emma Jeppsson, a customer in the store, said.

Produce stickers, which are made of paper or plastic along with ink and adhesives, may seem like more of an inconvenience than a source of pollution, but environmentalists say even small bits of waste have an impact on the environment.

"We know there's a huge amount of waste across the supply chain before we get to the packaging we see on our shelves," Friends of the Earth campaigner Kierra Box said.