Whether you live in the United States or Denmark, Germany or Ireland, chances are you’d like to see more manufacturing in your own country. But on the face of things, it’s hard to argue with offshoring.

For many countries, overseas labor rates are far lower than those of domestic sources. There are fewer concerns over employee unions or strict government regulations when parts are offshored. Even with shipping costs, tariffs, and a few trips to check on foreign suppliers, piece part prices from these sources are often a fraction that of local production. Sure, lead times are longer, but keeping the supply chain full is a matter of accurate demand planning—a simple task for the corporate software system, right?

Maybe not. Manufacturers have used these and similar offshoring arguments for decades, often with unexpected results. What initially promised to be an easy bump to the bottom line soon became fraught with quality problems, late deliveries, hijacked intellectual property, and urgent after-hours telephone conferences with managers in different time zones.

The occasional factory visit became an application for a six-month foreign worker visa to get the plant back under control. Rework costs skyrocketed and profits fell, while companies reminisced about the days of predictability, quick deliveries, and self-determination.

David Newell, Director of Sales at Dynisco, meets with attendees of the 2015 National Plastics Expo at Dynisco’s booth. Dynisco produces for global markets in the U.S., Europe and Asia.Dynisco

David Newell, Director of Sales at Dynisco, meets with attendees of the 2015 National Plastics Expo at Dynisco’s booth. Dynisco produces for global markets in the U.S., Europe and Asia.Dynisco

Peanut Butter & Politics

What went wrong? Matthew Miles will tell you these companies failed to understand their products’ total cost of ownership (TCO) before making strategic sourcing decisions. “All too often the people responsible will calculate the easy things like shipping rates, labor and material costs, and say, ‘Oh, wow. It’s cheaper over there.’ Unfortunately, the things they overlooked—the cost of quality, additional warranty and service expense, travel expenditures, increased inventory, and so on—these all go into corporate overhead, which is then ‘peanut buttered’ across the entire organization.”

The real problem is what comes after. Because there is now less manufacturing work being done at home, equipment is sold off and workforces reduced. The peanut butter is spread across fewer assets, disproportionately burdening the remaining segment of the business with misplaced costs. Adding insult to injury is the need for overburdened employees to rework foreign-made goods, or travel to distant plants to support operations there.

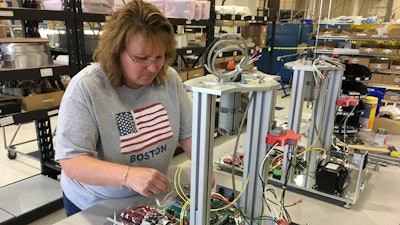

Kim Deforest, Polymer Test Cell Assembly, is assembling a Laboratory Melt Indexer base unit at Dynisco’s Franklin, MA plant.Dynisco

Kim Deforest, Polymer Test Cell Assembly, is assembling a Laboratory Melt Indexer base unit at Dynisco’s Franklin, MA plant.Dynisco

“Hopefully, that outdated business model is changing,” says Miles. “With proper use of TCO, companies can avoid these problems, and make intelligent decisions on the best place to manufacture their products.”

Miles is the DFMA (Design for Manufacturing and Assembly) and Value Engineering Manager at Massachusetts-based Dynisco Instruments, a leading manufacturer of testing and control products for the plastic industry. This includes pressure and temperature gauges, rheometers for evaluating in-process material flow, rupture disks to assure safety during molding and extrusion, and a variety of instrumentation and accessory equipment.

For nearly two decades, Miles has been a champion of TCO and DFMA, and has been responsible for reducing costs and “right sourcing” manufactured products at Dynisco and a number of sister companies over the past six years. He is also a power user of DFM and DFA software from Boothroyd Dewhurst Inc. (BDI), Wakefield, R.I., in use at Dynisco since 2009.

Dave Azevedo, Global Support Manager, sets a weight on the piston assembly of a Dynisco Laboratory Melt Indexer at their Franklin, MA facility.Dynisco

Dave Azevedo, Global Support Manager, sets a weight on the piston assembly of a Dynisco Laboratory Melt Indexer at their Franklin, MA facility.Dynisco

From Malaysia to the Midwest

Miles points to a recent project on a material analyzer product at a sister company—a tabletop test instrument used for analyzing material during processing—as a perfect example of the analytical power that TCO and DFMA bring to manufacturing companies.

His value analysis/value engineering (VAVE) Group at Dynisco provides cost analyses at a corporate level, and the team recently evaluated the labor and overhead rates at three locations in order to determine which would be the most cost-effective to produce the material analyzer:

- A sister facility in the Midwest that produces similar test equipment.

- A manufacturing and distribution site in Malaysia that specializes assembly work such as bonding and wiring of strain gages.

- A manufacturing and distribution site in China responsible for various sensors, valves, and safety devices across a number of Dynisco’s sister companies.

The initial results came as no surprise to anyone. Comparing scaled rates, with a US labor rate of $30/hour, there was no chance to compete with China’s hourly wage of $4.15, and Malaysia at $1.85/hour. Even after accounting for higher overhead rates as a percentage of labor cost, the two offshore facilities came in with product costs 23 percent and 24 percent lower respectively.

Yet Miles knew these numbers represented the old-school way of thinking. Using a series of user-definable fields in Boothroyd Dewhurst’s DFA software, he defined additional TCO factors to account for the cost of poor quality, remote supplier management and project transition expenses, packaging, lead time and transportation costs, intellectual property loss, and other risk considerations traditionally left out of outsourcing decisions.

When complete, the TCO analysis still pointed the Midwest company towards overseas sourcing, but not by much—the Malaysia facility was now favored by just 9 percent.

Data of the existing material analyzer product cost structure, as manufactured in the U.S. before DFMA redesign. The baseline numbers are representative, not actual numbers.Dynisco

Data of the existing material analyzer product cost structure, as manufactured in the U.S. before DFMA redesign. The baseline numbers are representative, not actual numbers.Dynisco

“I received the request from management to analyze the product using TCO and DFMA,” Miles explains. “The question was, should this product be built at one of our low-cost manufacturing sites overseas for cost reduction? And what are the opportunities to reduce the cost of this product based on the DFMA analysis? We’d been building the product in the Midwest for some time, so we had a good baseline to start with. After the initial pre-TCO analysis, anyone would have looked at the results and said we should move it immediately to the facility in Malaysia. But by the time we were done accounting for all of our TCO values—especially the risk of intellectual property loss, which we calculated at 100 percent—keeping it in the Midwest was clearly the best choice, even though offshoring remained a bit cheaper.”

Still, many would argue that a 9 percent cost reduction is nothing to sneer at, despite the risks. This was a figure, however, that Miles was confident he could make up with a little DFMA analysis. During a two-day deep dive workshop Miles, and fellow engineers from the Midwest company and VAVE Group, used Boothroyd’s DFM and DFA tools to peel away roughly $2,000 in product redesign and supply chain “should costs” on each material analyzer built. The end result: A 17 percent baseline improvement by continuing production in the Midwest—8 percent more cost-effective than Malaysia.

Cost breakdowns of manufacturing in the U.S., China, and Malaysia without considering total cost of ownership.Dynisco

Cost breakdowns of manufacturing in the U.S., China, and Malaysia without considering total cost of ownership.Dynisco

Cost breakdowns of manufacturing in the U.S., China, and Malaysia after considering TCO.Dynisco

Cost breakdowns of manufacturing in the U.S., China, and Malaysia after considering TCO.Dynisco

Breaking Silos

For those considering TCO analysis, garnering support across multiple levels of the organization is a necessary first step. A subject matter and project team should be selected—people who can work with finance, purchasing, engineering, and other departments to gather data and share ideas and opinions on the various costs that go into making the target product. And support from upper management is critical—Miles says that grass roots TCO initiatives, while noble, are often doomed to failure.

In Dynisco’s case, executive endorsement came right from the top. President John Biagioni once managed Viatran, a “worldwide maker of pressure and level transmitters” and an aggressive user of TCO, something that Biagioni fully implemented. His background includes engineering, economics, and machining—as Miles explains it, “He’s an executive who knows how to machine parts.” Because of this, Biagioni is one of TCO’s biggest supporters at Dynisco.

Despite this, Biagioni maintains he’s agnostic on the subject of reshoring; to him, it’s all about the numbers. “John’s a firm believer in build-where-you-sell, but that doesn’t mean he’s going to take a loss just so he can say a product was built in the Midwest, or anywhere else for that matter,” explains Miles. “He knows the companies that do so lose in the long run and sometimes they lose big.”

TCO datafields showing the numerical values of risks—i.e. health pandemic, IP transfer of manufacturing in the U.S.

TCO datafields showing the numerical values of risks—i.e. health pandemic, IP transfer of manufacturing in the U.S.

TCO datafields showing the numerical values of risks—i.e. health pandemic, IP transfer of manufacturing in China.Dynisco

TCO datafields showing the numerical values of risks—i.e. health pandemic, IP transfer of manufacturing in China.Dynisco

Do the Math

Miles says one of the most unfavorable impacts of building parts away from home—and a frequently overlooked point when deciding to do so—is its effect on continuous improvement. “For most US-based companies, the engineering team is here in the states,” he says. “That presents opportunities for DFMA workshops and brainstorming sessions that otherwise wouldn’t take place when you’re working across multiple time zones. And anytime you modify a product design, you’re probably looking at new quotes from suppliers, additional DFM on downstream parts, and there are always issues that crop up that would be difficult to resolve without an engineer or product designer onsite. The process as a whole is far more manageable if done in-house.”

That process is also dependent on transparency. Engineers and accountants alike must understand where the numbers come from when doing TCO calculations, and agree with them. And once a decision has been made, it’s important to know its impact on next year’s numbers, and the years after that.

“The biggest eye openers for us were the Life Volume Costs that are calculated in DFA,” Miles notes. “For industrial products with life cycles of a decade or longer, DFMA-based cost reductions can quickly translate into millions of dollars—in one recent workshop, we estimated more than 20 million net savings on a single product line over the next few years.”

Keeping work in-house often helps absorb overhead costs as well. Miles mentions another example where DFMA was used to justify moving product assembly from a different site back to Dynisco’s Franklin, Mass. facility. Because DFA identified ways to streamline the manufacturing process, revenue was added without increasing shop floor headcount, thereby improving plant efficiency.

Becoming a Believer

Miles says DFMA, TCO, and Value Engineering are viewed by many in the industry as “specialty cost reduction” tools, good for trimming away the fat on existing products but not an inherent part of the design process. “Nothing could be further from the truth,” he says. “These tools are about optimizing product costs while maintaining function and quality. Yes, the techniques are also valuable for legacy parts, but their biggest value is realized when put into play right up front, and used as everyday tools.

“You have to participate in the process of DFMA and TCO and experience the results of applying the tools for yourself,” he summarizes. “Once you’ve applied the techniques and can see before-and-after product designs, then tally up the annual cost savings for the company, you’ll become a believer. Properly applied, DFMA optimizes a product long before the first prototype is ever made, eliminating changes later on. Adopting it early in the design process also increases user acceptance. Regardless, there has to be strong support from management for any DFMA/TCO initiative to succeed. It can be a challenge to change company culture, and there needs to be clear, consistent pressure applied in a positive manner to send the message that DFMA integration is all about increasing profits and building a strong company.”