LONDON (AP) — Nearly a third of U.K. firms may shift their operations abroad because of Britain's looming departure from the European Union, a survey of 1,200 company directors suggested Friday, as the political stalemate over a Brexit deal heightened jitters among businesses.

The survey by the Institute of Directors, an employers' group, found that 16 percent of businesses already had relocation plans while a further 13 percent were "actively considering" a move.

The group said while headlines have focused on big companies, less notice has been given to smaller U.K. businesses and their plans to relocate.

Institute interim director Edwin Morgan said smaller firms typically have tighter resources and for them "to be thinking about such a costly course of action makes clear the precarious position they are in."

Britain is due to leave the EU on March 29, but a Brexit divorce agreement struck between British Prime Minister Theresa May's government and the bloc late last year as been rejected by Britain's Parliament.

U.K. lawmakers voted this week to send May back to Brussels to seek changes to the divorce agreement. But the EU is adamant that the deal cannot be renegotiated, leaving Britain lurching toward a cliff-edge "no-deal" departure from the bloc that many businesses fear will cause economic chaos.

A survey of companies released Friday showed that manufacturing firms stockpiled goods at a record rate in January to prepare for potential Brexit disruption to trade.

The survey of about 600 U.K. manufacturers by the market research company Markit and the Chartered Institute of Procurement and Supply found that inventories of finished goods rose sharply, while optimism in the sector was at a 30-month low and jobs were starting to be cut.

Senior government ministers have suggested that Britain may have to seek a delay to Brexit to make time to find a solution.

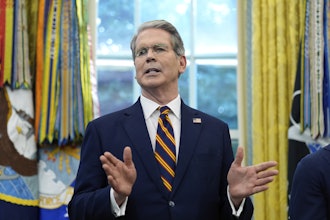

International Trade Secretary Liam Fox said Friday the government was "still aiming to get to the 29th March — that's the date we promised the British people." But he suggested there could be "a short delay" if Britain and the EU "had reached an agreement and needed the legislation to implement it."

A delay would need the approval of the 27 remaining EU states. Ireland's Europe Minister, Helen McEntee, said the bloc would likely agree, as long as Britain had a good reason.

"There is no point in looking for an extension if we end up back to the same place in three months' time," she said. "We need to have a clear direction from the U.K. government as to what it is we want to achieve."

The sticking point to a deal for many British lawmakers is a border measure known as the "backstop," a safeguard mechanism that would keep the U.K. in a customs union with the EU to remove the need for checks along the border between the U.K.'s Northern Ireland and EU member Ireland after Brexit.

The border area was a flashpoint during decades of conflict in Northern Ireland that cost 3,700 lives. The free flow of people and goods across the near-invisible border today underpins both the local economy and Northern Ireland's peace process.

Many pro-Brexit British lawmakers fear the backstop will trap Britain in regulatory lockstep with the EU, and say they won't vote for May's deal unless it is removed.

May has been sounding EU leaders out on potential changes, but Britain's stance has caused exasperation among EU politicians, who point out that May signed up to the deal that she is now seeking to change.

"This was a deal that was negotiated with the U.K., by the U.K.," McEntee said. "They weren't bystanders in a separate room. There were discussions, negotiations. There were compromises on both sides."

Diplomats have also warned that British attempts to reopen the agreement could trigger moves by EU nations to get concessions from the U.K. on issues including fishing rights and, particularly, Gibraltar.

Throughout divorce talks, Spain has stressed that it wants a say on the future of the disputed British territory at the tip of the Iberian peninsula.

Tensions over the territory flared again Friday, as Britain expressed irritation at an EU document describing the rocky outcrop as a British colony.

The phrase occurs in a document outlining the bloc's intention to continue allowing British citizens visa-free travel for short stays even if the U.K. leaves the bloc without a deal. A footnote refers to Gibraltar, which was ceded to Britain in 1713 but is still claimed by Spain, as "a colony of the British Crown" and says there is "controversy" over its sovereignty.

Spanish government spokeswoman Isabel Celaa noted Friday that Spain still claims sovereignty over Gibraltar.

But May's Downing St. office said it was "completely unacceptable" to describe Gibraltar as a colony, calling it "a full part of the U.K. family."