BAYTOWN, Texas (AP) — Joel Johnson examines the shipping labels on 35-ton coils of American-made steel that will be unspooled, bent and welded into rounded sections of pipe.

One's from Nucor, a mill in Arkansas. Another's from Steel Dynamics in Mississippi. But much harder to spot in the sprawling factory yard is the imported steel that's put his company in the crosshairs of President Donald Trump's bitter trade dispute with America's allies and adversaries.

Trump says his tariffs on steel, aluminum and other goods will put U.S. companies and workers on stronger footing by winding back the clock of globalization with protectionist trade policies. But the steel tariff — essentially a 25 percent tax — may backfire on the very people the president is aiming to help. The Commerce Department has been deluged with requests from 20,000 companies seeking exemptions.

Johnson is the CEO of Borusan Mannesmann Pipe US, a company with Turkish roots that manufactures the welded pipe used by energy companies to pull oil and natural gas out of the earth. He has been fighting an uphill battle to get a two-year exemption from Trump's tariff on steel imports.

Without a waiver, Johnson said, Borusan faces levies of up to $30 million a year — a staggering sum for a business with plans to expand.

"We don't have any proof we're being heard," Johnson said.

Eighty miles southwest, in Bay City, global steel giant Tenaris also is seeking an exemption from the tariffs. The company churns out steel pipe in a $1.8 billion state-of-the-art facility that began operating late last year, using solid rods of steel called billets that are made in its mills in Mexico, Romania, Italy and Argentina. Of the four, only Argentina has agreed to limit steel shipments to the U.S. in exchange for being spared the tariff.

"The decision is out of our hands," said Luca Zanotti, president of Tenaris's U.S. operations, while expressing confidence its request would be approved. If it's not? "We'll adapt," he said.

Steelworkers, meanwhile, are cheering the tariff even as they remain skeptical of Trump's pledge to empower blue-collar Americans. They also worry about the possibility of too many exemptions.

"You put these tariffs (in place) but now you're going to exclude everybody so they're kind of pointless," said Durwin Royal, president of United Steelworkers' Local 4134 in Lone Star, Texas.

The diverse views illustrate the complexity, confusion and concern lurking behind Trump's "America First" pledge.

Pipe mills are numerous in Texas, which leads the country in oil and natural gas production. Factories that use imported steel typically do so when they can't get the exact type or quantity they need from U.S. producers. Many of them are among the thousands of companies that have filed exclusion requests to avoid being hit by the steel tariff.

Most of them are in the dark, unsure if their applications will be approved as the Commerce Department struggles to process a dramatically higher number of requests than it expected to receive.

A denial may torpedo plans to expand a factory. Or a company may have to lay off employees. The stakes are especially high in Texas: Economists Joseph Francois and Laura Baughman have estimated the Trump steel tariff and separate 10 percent tariff on imported aluminum will trigger the loss of more than 40,000 jobs.

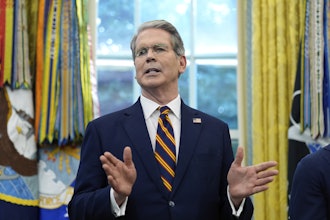

There's no playbook to guide companies through an exemption process Johnson described as chaotic and unpredictable. He's hired a lobbyist, former New York Gov. George Pataki. He's fending off opposition from competitors, including a Tenaris-owned business, who want Borusan's request denied.

On a sweltering afternoon earlier this month, Johnson assembled dozens of his employees in an air-conditioned room for what amounted to a Hail Mary pass. After lunching on sandwiches from Chick-fil-A, Borusan workers wrote personal messages on oversized postcards to be sent to Trump and other senior officials in Washington and Austin, the Texas capital, pleading for their help in securing the tariff exemption.

"I don't know what motivates politicians besides votes," Johnson said. "That's why we're doing this crazy exercise."

___

UNION BLUE

Royal is in his third term as the president of Local 4134.

He and the local's vice president, Trey Green, are union Democrats in the heart of Trump country. Lone Star is in Morris County, Texas, where Trump received nearly 70 percent of the vote in the 2016 presidential election. Royal and Green initially backed independent Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders before casting their votes for Democrat Hillary Clinton.

Their union hall is a mile and a half from the U.S. Steel factory that manufactures welded pipe made from metal produced in the company's mills in Indiana and Illinois. Like the union, U.S. Steel backed Trump's tariff, declaring that his action would "level the playing field" by blocking other countries from dumping inexpensive steel in the United States. Much of it comes from China.

Although Royal and Green were heartened by the steel tariff, they said they're under no illusion Trump is a friend to organized labor. Nor are they convinced his tough talk on trade will lead to a rebuilt U.S. steel industry with more and better jobs. Echoing Sanders, they called for a broader strategy to prevent corporations from sending American jobs to low-wage countries.

"I don't know that putting tariffs on just one or two particular items are going to be the mainstay that helps us in the future," Green said.

Royal and Green said they're still waiting for Trump to follow through on his pledge to empower working-class Americans that he said were "forgotten" by Washington.

"So much money is in politics now it's kind of drowning people like us out," Royal said. "We're not going to take (a congressman) to dinner and buy him a new set of golf clubs or give $250,000 toward his campaign. You can tell who's got the loudest voice there."

___

COST OF DOING BUSINESS

The Tenaris factory is a massive, modern facility just off the highway leading into Bay City, 21 miles from the Gulf of Mexico. About 640 people work here, but only a handful come into direct contact with the 50,000 tons of pipe the 1.2 million-square-foot factory is able to manufacture each month. The process is almost entirely automated, watched over by employees huddled in front of computer screens.

The company manufactures seam-free pipe typically used in offshore energy production or for transporting highly corrosive gas.

Tenaris began construction of the Bay City plant five years ago, long before anyone anticipated an American president would slap a tariff on steel. Zanotti declined to say how much Tenaris may have to pay, but he downplayed the expense as a cost of doing business on a global scale. Tenaris operates in 16 countries, including Nigeria, which ranks 145 out of 190 countries on the World Bank's "ease of doing business" index.

"Of course we don't like it," Zanotti said of the tariff.

But, he added, "we're used to dealing with moving parts. This is another moving part."

The company doesn't have a registered lobbyist in Washington, let alone an office. But Tenaris has deep pockets and is in the U.S. for the long haul.

Zanotti said the company has spent $8 billion over the last decade to expand its foothold in America, a figure he doesn't think the Commerce Department should overlook. The investment includes the Bay City factory and the acquisition of the Maverick Tube Corporation, based in Houston. Like Borusan and U.S. Steel, Maverick makes pipe with a welded seam.

"We're positive we're going to get a good conclusion," Zanotti said.

___

LET'S MAKE A DEAL

Johnson said he has a proposition for a president who prides himself on being a master dealmaker.

About 60 percent of Borusan's welded pipe is manufactured with American-made steel. The rest is shipped from Turkey already in tube form; it's heat-treated, threaded and inspected in Baytown. Johnson is proposing that Borusan be allowed to bring in 135,000 tons of Turkish pipe each year for the next two years, tariff-free. In return, the company will build a new factory, right next to its existing plant.

That's a $75 million investment that will allow Borusan to hire 170 new employees, augmenting its existing workforce of 267, according to Johnson. The expanded capacity also will allow Borusan to wean itself from the Turkish imports. He said he's gotten no reply to his pitch.

The company brought ex-Gov. Pataki, a Republican, on board in March and has paid him $75,000 to drum up support in Washington. But Johnson said he's unsure if Pataki's made a difference.

"We're not politicians. We make pipe," he said. "We felt like that was a move we had to make because we are so far out of our element."

Johnson said he had for weeks unsuccessfully sought support from GOP Rep. Brian Babin, whose district includes Baytown. Babin wrote to Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross on Thursday, expressing his strong support for Borusan's request and urging Ross to give it "your highest consideration."

"Finally," Johnson said.

The Commerce Department has been posting the thousands of requests for tariff exemptions online to allow third parties to offer comments and objections — even competitors who have an interest in seeing a rival's request denied. Several of them, including U.S. Steel and Tenaris-owned Maverick Tube, objected to Borusan's bid, saying the Turkish pipe it imports is readily available from American suppliers. They added that Turkey has been cited by the Commerce Department for dumping steel pipe in the U.S.

But Johnson said the objections are aimed at undercutting Borusan. He said no U.S. pipe mill is serious about selling to him because he'd want very detailed information about their products — such as the composition of the steel and a history of customer complaints.

"They just don't want to see another factory go up here," Johnson said. "They don't want to see a competitor grow."