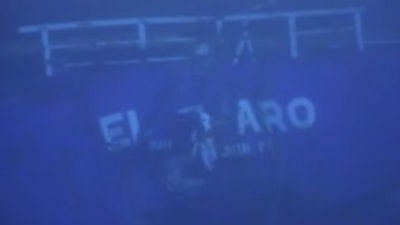

The El Faro sank (wreckage video below) just before it was to be added to a Coast Guard list of vessels identified as having the most "potential for risk," a designation that would have triggered more safety inspections.

The El Faro was to be included on the so-called "targeting list," which compiled the top 10 percent of ships the Coast Guard believed needed stricter scrutiny, U.S. Coast Guard Capt. Kyle McAvoy testified Monday during an investigative hearing.

But the 40-year-old El Faro sank in 15,000 feet of water after losing propulsion and getting caught in Hurricane Joaquin just days before the Coast Guard planned to send the ship's owner a message about the new designation. All 33 people aboard died.

When news of the ship's disappearance came in, McAvoy said the connection was immediately made.

"The question became, internally, 'What do we do now? We just lost the El Faro,'" McAvoy said. "We held the message."

The Coast Guard did release the list with El Faro's name still on it after confirming it sank. He did not say why, specifically, the ship was on the list but said age, expired documents or other problems are reasons other ships make the list.

McAvoy's revelation came during testimony on the sixth day of the Coast Guard's investigative hearing in Jacksonville looking into the El Faro's sinking. Investigators are looking into whether misconduct played a role in the ship's sinking, including whether mistakes were made in inspections. Coast Guard and National Transportation Safety Board investigators are participating in the hearing, and will release separate reports.

In his final call for help, Capt. Michael Davidson told company officials he'd lost propulsion and his engineers could not fix it. He said water was flowing into one of the ship's holds, and the vessel had a "heavy list," or tilt.

Previous testimony showed that the ship, owned and operated by Tote Inc., was due for its boilers to be serviced the month after it sank. Documents showed the boilers contained parts inspectors said had "deteriorated severely" before the ship's voyage from Jacksonville to Puerto Rico.

Still, Tote officials who reviewed those inspection reports described the scheduled maintenance as routine and that nothing identified in the boilers caused safety concerns, according to testimony.

Monday's hearing also focused on data gaps in the safety inspection system for commercial shipping. Coast Guard Capt. John Mauger said that his office identified a "disturbing" uptick in safety discrepancies found during vessel inspections between 2013-2014.

Mauger said that more than 90 percent of ship inspections are performed by private classification societies, mainly the American Bureau of Shipping, or ABS, and that there are reporting "gaps" in the information these groups share with the Coast Guard. The bureau of shipping did full hull and machinery inspections in February with no red flags, the company has said.

Because of this data gap, Mauger said it is difficult to fill cracks in the system that may be allowing risky vessels to go to sea. He said they are working to fix communication between the Coast Guard, ABS and other classification societies.

"We don't know what we don't know. If they don't notify us ... we see that as a gap," Mauger said.