Sure, Formula E teams want to win and make money. That's a given. The big automobile manufacturers who fund the open-wheel electric cars that whir around tracks all over the world also have a bigger goal in mind: research and development.

Brand named automakers — from BMW to Audi to Jaguar — compete to create the best technology for their race cars, which look like the more popular, gas-guzzling Formula 1 racers but are powered by rechargeable batteries. The high-performance engineering is then used as a case study for the development of consumer car lines.

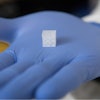

It's a constant intellectual race to find the cheapest and highest-performing material for racing. Formula E regulations ensure it. Each car must be physically the same. The only difference between the cars is their electric battery. Developing the most efficient energy source is how teams win. That innovation is in turn used to develop cheaper consumer cars.

The same minds behind BMW's i3 and i8 electric cars are behind the manufacturer's Formula E team. That synergy between racing and consumer design is uniform across Formula E, which will finish its fifth season on Sunday in Brooklyn.

And other luxury car companies who fund teams in traditional racing leagues are catching on: Mercedes and Porsche will join Audi, BMW and Jaguar on the Formula E circuit next year.

In just five years, work in the Formula E lab has led to concrete change in consumer electric automobiles.

Audi recently unveiled a car with an 800-volt battery system based on technology it developed from its Formula E team. All current cars on the market are under 400 volts. A higher volt count means more efficiency, less weight and quicker charging. It also means, at a baseline level, cheaper cars.

"The next generation of electric cars will be using that level of voltage," said Sylvain Filippi, Virgin Racing's chief technology officer.

Filippi stressed that Virgin Racing is a "renewable energy company that goes racing."

"If this was Formula 1, I wouldn't be doing it," he told The Associated Press. "I wouldn't be interested."

The International Energy Agency projects that 125 million electric cars will hit the road by 2030, up from 5.6 million in 2019.

The leading manufacturers know that, in order for electric cars to take hold in broader society, governmental incentive is important, but advancement must start with the producers. Developing cheaper, more efficient cars will lead to more people buying them, which then puts more clean-energy automobiles on the streets. It's a method that Formula E thinks can incrementally combat climate change.

"We are getting enormous technology feedback from there," Dilbagh Gill, CEO of Mahindra Racing, said in a statement. "Formula E is our laboratory."

But, of course, basic economics take precedent, and the manufacturers in Formula E have not yet perfected that part of the equation. It is still not universally cost efficient for the basic consumer to invest in an electric car.

The average cost of an EV in 2018 was $38,775, according to a study conducted by Kelley Blue Book. For gas-powered vehicles, that cost was just over $20,000.

"It's sad, but we're in a world where you need to make the economic case work for everyone, otherwise we will not make progress," Formula E CEO Alejandro Agag said on a panel Friday. "People sadly are not going to do it for the good of people. They're going to do it when there is a real economic gain for everyone."

Formula E's drivers know they are small players in a broader sociopolitical battle to normalize electric cars. Many are on board with the arrangement.

"It's extremely good for all of us," Nissan's Oliver Rowland said.

BMW racer Alexander Sims is also on board. He stressed that governments must subsidize the current gap in price between electric and gasoline-driven vehicles. He used Norway as an example, where electric vehicles have the largest presence per capita in the world, according to the Norwegian Information Council for Road Traffic.

"The incentives are there for installing charging points at home and the cost of the EV initially is supported as such," Sims said. "You see in Norway, when the policies are right, EVs outsell regular cars."

Many drivers emphasized that creating eye-catching cars is the true first step to increasing EVs' market share.

"My biggest goal and duty is to prove that electric cars are exciting, fun, cool, fast and sexy," said Alex Lynn, Jaguar's Formula E racer.

"I think it's important to show the younger generations that EVs are cool, exciting and fun. And fast and reliable," Virgin's Sam Bird added. "Because in 10 years' time, they're going to be driving EVs."