In hills where Zulu royalty once hunted wildlife, South African conservationists now scan live video from a thermal-imaging camera attached to a drone, looking for heat signatures of poachers stalking through the bush to kill rhinos.

The unarmed drone, which resembles a model airplane, flies several miles from a van where an operator toggles a customized video-gaming control, zooming and swiveling the craft's camera.

The nocturnal surveillance in Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Game Reserve comes amid international discussion about whether technology, particularly drones, will make a real difference in anti-poaching efforts that often rely on the "boots on the ground" of rangers on patrol.

Several years ago, drones were touted by some as a silver bullet for conservation, but some experiments have floundered. Even so, drone technology is developing quickly and the aircraft have been used around the world, including:

- In Belize, where the Wildlife Conservation Society helped deploy drones to successfully monitor a protected reef area for illegal fishing, according to David Wilkie, director of conservation measures for the group.

- In Indonesia, where drones have surveyed threatened orangutan habitats.

- In Africa, where the World Wildlife Fund is exploring the use of drones and other anti-poaching technologies, using funding from Google.

"It's a very dynamic battle space where the poachers are continually responding to advances in technologies," said Arthur Holland Michel, co-director at the Center for the Study of the Drone at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York.

Poachers could, for example, seek vegetation cover to try to avoid being spotted by drones or use informants to monitor drone teams and learn when the skies are clear.

"They have great potential," Wilkie said of drones. "I think they're not there yet."

Wilkie said groups with limited budgets often opt for types of drones used by hobbyists. A military-grade, aluminum drone with a powerful engine and sophisticated radar that can look through canopy and detect metal — a poacher's car or motorcycle, for example — could be more effective, he said.

Searching for poachers with drones in Africa's vast wildlife reserves can seem like a needle-in-a-haystack operation. Costs mount, crashes are frequent, equipment breaks down, rain or high wind can scrap a mission and even before operations start, legal and bureaucratic obstacles must often be overcome in countries that tightly regulate airspace.

In a drone mission in Hluhluwe-iMfolozi recently observed by an Associated Press team, operators looked for heat-emitting objects that appear white and vertical on the screen, similar in shape to a rice grain. Three vertical rice grains are a giveaway because poachers often work in threes — a tracker, a shooter with a heavy-caliber rifle and a carrier with supplies and an axe to hack off rhino horn for eventual sale on an illegal Asian market.

The operators didn't spot any suspected poachers or need to notify rangers by phone or radio, though they saw horizontal heat signatures from wildlife, including a rhino and a calf. Flights can last more than two hours, focusing on perimeter fences and other areas where poachers might be.

"All we've learned to do is to fly and to live in the bush. It can only get better from here," said Otto Werdmuller Von Elgg, director of UDS, a fledgling South African firm that operates the drone team in Hluhluwe-iMfolozi. It has another at Kruger National Park, the country's biggest wildlife reserve, which is almost the size of Israel.

Poaching levels dropped in some areas where UDS flew and picked up after it left, possibly indicating poachers were scared by the drones, according to Von Elgg. He said he worries about possibly corrupt park staff who might tip poachers to drone team whereabouts and flight times.

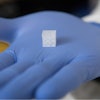

Each UDS drone has a composite foam fuselage and a 7.9-foot (2.4-meter) wingspan, relying largely on durable, off-the-shelf technology and costing about $12,000, half of which is for the camera.

UDS gets support from the Lindbergh Foundation. According to its website, the foundation, based in Berkeley Springs, West Virginia, is "dedicated to the elimination of illegal poaching of elephants and rhinos in southern Africa using cutting edge software-based predictive analysis and drones."

One drone team costs up to several hundred thousand dollars to operate a year. Foundation chairman John Petersen said the long-term goal is to attract $25 million in annual funding for more than 40 teams in Malawi, Zambia and other African nations that have expressed interest.

Bathawk Recon, an anti-poaching drone company in Tanzania, has conducted trials of hand-launched aircraft.

"There is general agreement that aerial surveillance will be a part of all effective anti-poaching strategies," Michael Chambers, Bathawk Recon's director of strategy and communications, wrote in an email. "How to deliver it is the question of the day.