WASHINGTON (AP) — With the nation's unemployment rate at its lowest point since human beings first walked on the moon, you might expect the Federal Reserve to be raising interest rates to keep the economy from overheating and igniting inflation.

That's what the rules of economics would suggest. Yet the Fed is moving in precisely the opposite direction: It is widely expected late this month to cut rates for the third time this year.

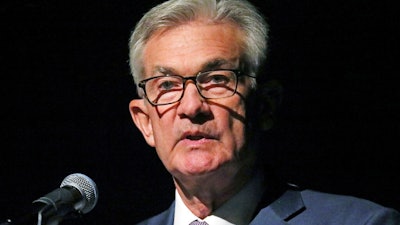

Welcome to the strange world that Jerome Powell inhabits as chairman of the world's most influential central bank. Though unemployment is low, so are inflation and long-term borrowing rates. Normally, all that would be cause for celebration. But with President Donald Trump's trade wars slowing growth and overseas economies struggling, Powell faces pressure to keep cutting rates to sustain the U.S. economic expansion.

"It's a very hard position for the Fed to be in," said Diane Swonk, chief economist for Grant Thornton, a consulting firm.

When Powell speaks Tuesday afternoon at an economics conference in Denver, his remarks will be scrutinized for any hints of the Fed's next steps.

One illustration of the Fed's unusual dilemma: The unemployment rate is now 3.5%, the lowest level since 1969. The Fed's benchmark short-term rate stands in a range of just 1.75% to 2%. By comparison, the last time unemployment fell below 4% — in 2000 — it raised its key rate to 6.5% to try to control inflation, which normally rises as unemployment falls. Having its benchmark rate that high also gave the Fed room to cut rates once a recession hit the next year.

Today's economic landscape is dramatically different. The same forces that are depressing growth and inflation and limiting pay growth are also boxing in the Fed: Slowing population growth and sluggish worker productivity are restraining the economy's ability to expand.

Online shopping, international competition and a more frugal consumer have held down inflation. A weak pace of growth and undesirably low inflation have forced the Fed to keep borrowing costs historically low. Once a downturn inevitably strikes, the Fed will have little ammunition left in the form of further rate cuts.

Persistently low interest rates are "the pre-eminent monetary policy challenge of our time," Powell acknowledged in June.

In response, the Fed has embarked on a far-reaching review of its monetary strategy and tools, which includes a series of public consultations known as "Fed Listens." Its initiative is a tacit acknowledgement by the Fed of its peculiar economic quandary.

"Fed Listens" sessions have been held by nearly all of the Fed's 12 regional banks. The sessions, attended by high-level bank staffers and sometimes Powell himself, have included labor advocates, community groups and academics specializing in worker training and education. The Fed says it will announce any changes to its strategies in the first half of next year.

One likely change, Fed watchers say, is the adoption of an average inflation target that the Fed would aim to achieve over time. Since 2012, the Fed has set an annual target of 2%. But it hasn't always been clear whether that is a ceiling or a more flexible goal.

Central banks around the world began adopting inflation targets in the early 1990s to help keep a lid on prices. Yet now most of them are struggling to reach their limits. Since adopting 2% as a target, the Fed has missed it nearly continuously, with annual inflation averaging just 1.4%, according to the Fed's preferred measure. In August, for example, U.S. prices excluding volatile food and energy costs rose 1.8% from a year earlier.

An average target would require the Fed to let inflation run above 2% to offset those times when it fell below the target. Otherwise, businesses and consumers would start to expect permanently lower inflation.

Those expectations can turn into reality: Businesses may, for example, respond by providing smaller cost-of-living pay raises, thereby making it even harder for the Fed to boost inflation. (The Fed seeks a low level of inflation as a cushion against a destructive fall in wages and prices.)

Supporters of average inflation targeting argue that it would help the Fed meet its objectives. Charles Evans, president of the Chicago Federal Reserve Bank, appeared to support this view in a speech last week.

"Engineering a modest overshoot of our inflation objective better guarantees that we would actually meet our inflation target in the future," Evans said.

Yet average inflation targeting isn't simple, Swonk notes. Given that the Fed has missed its objective for most of the past seven years, does that mean it should top 2% for seven years?

Carl Tannenbaum, chief economist at Northern Trust and a former Fed staffer, noted another concern: "If the Fed is having a hard time getting inflation to 2%, it would have an especially hard time getting it above that." And failing to do so could erode public confidence in the Fed.

Some Fed officials aren't that worried about where inflation is now.

Esther George, president of the Kansas City Fed, warned Sunday night that cutting rates further to try to lift inflation would risk inflating bubbles in stocks and other assets.

Other Fed officials back additional rate cuts because the Fed has appeared to worry too much about inflation in the past and has raised rates when unemployment still had room to fall. In 2014, for example, the Fed thought the unemployment rate wouldn't be able to fall below 5.4% without accelerating inflation. So in 2017, after unemployment fell below 5%, the Fed continued a series of rate hikes in part to ward off potential high inflation.

Yet now, with the unemployment rate at 3.5%, high inflation is nowhere in sight.

"We misread the labor market," Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari said earlier this year, "thinking we were at maximum employment when, in fact, millions of Americans still wanted to work."