TRAVERSE CITY, Mich. (AP) — Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder's administration and Canadian pipeline giant Enbridge announced an agreement Wednesday to replace twin 65-year-old crude oil pipes that critics have long described as an environmental disaster waiting to happen in a crucial Great Lakes channel.

The plan calls for decommissioning the pipes after installing a new line in a tunnel to be drilled through bedrock some 100 feet (30 meters) beneath the Straits of Mackinac, a more than 4-mile-wide (6.4-kilometer) waterway where Lakes Huron and Michigan converge. The massive engineering project is expected to take seven to 10 years to complete, at a cost of $350 million to $500 million — all of which the company would pay.

In the meantime, about 23 million gallons (87 million liters) of oil and natural gas liquids used to make propane would continue moving daily through the twin lines at the bottom of the straits. They are part of Enbridge's Line 5, which extends 645 miles (1,038 kilometers) from Superior, Wisconsin, to Sarnia, Ontario, crossing large areas of northern Michigan.

The state and Enbridge described the agreement as a win-win that eventually would get rid of the twin lines, removing the threat of a spill that studies have said could despoil the lakes and shorelines for hundreds of miles.

"This common-sense solution offers the greatest possible safeguards to Michigan's waters while maintaining critical connections to ensure Michigan residents have the energy resources they need," Snyder said.

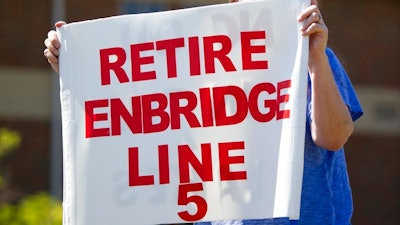

Environmental groups criticized it for failing to shut down the existing pipes quickly and accepting oil transit through the straits area indefinitely.

"We know that Line 5 is a threat to the Great Lakes and our way of life now whereas a tunnel, if it is ever built, is many years away," said Mike Shriberg, regional director of the National Wildlife Federation. "The communities, businesses, water, and wildlife that would be lost if Line 5 ruptures cannot be replaced."

Enbridge insists the pipes are in good condition and could be used far into the future. But the company has been on the defensive in recent years following discoveries of dozens of spots where protective coating has worn off, plus damage from a ship anchor strike last April.

Spokesman Ryan Duffy said the company, based in Calgary, Alberta, "has operated Line 5 safely and reliably for decades" and cooperated with state regulators, although Snyder and other officials previously have accused Enbridge of being less than forthcoming — particularly about the coating gaps.

"We believe this agreement makes a safe pipeline even safer," Duffy said.

The deal, reached as Snyder's term winds down, is sure to be a contentious issue in the campaign to succeed him. Democratic nominee Gretchen Whitmer has pledged to shut down Line 5 if elected governor in November. Her Republican opponent, state Attorney General Bill Schuette, has endorsed the tunnel option.

It wasn't immediately clear whether the next administration would have legal authority to undo the agreement. Michigan owns the straits bottomlands and granted Enbridge an easement when the pipes were laid in 1953. Keith Creagh, director of the state Department of Natural Resources, said any effort to revoke the easement would trigger a lengthy and expensive court battle.

But opponents argued the agreement isn't legally binding because it calls for further negotiations on key details, including the design, construction and operation of the tunnel. Creagh said officials hope to reach agreement on the unsettled issues before Snyder leaves office at year's end.

Among them: creating a public-private partnership between Enbridge and the Mackinac Bridge Authority, the state agency that oversees the suspension bridge traversing the straits between Michigan's upper and lower peninsulas near the underwater pipes.

Under the deal, the bridge authority would help Enbridge obtain government permits for the tunnel and replacement pipeline and would assume ownership of the tunnel when completed. The agency would lease the tunnel to Enbridge for its pipeline and could work out similar arrangements to house electric and telecommunications cables.

State officials say the bridge authority's original mandate in 1952 envisioned the possibility of managing tunnels. But environmental attorney Jim Olson, president of a group called For Love of Water, said the authority could not legally operate a tunnel "that has nothing to do with vehicles." He said the agreement raises "serious legal issues."

The plan includes provisions intended to reduce the likelihood of a leak from the existing pipes while the tunnel is built and to ensure close collaboration between Enbridge and the state after the new pipeline becomes operational, officials said.

Among them: underwater inspections to detect potential leaks and evaluate pipe coating; placement of cameras at the straits to monitor ship activity and help enforce a no-anchoring zone; a pledge that Enbridge personnel will be available during high-wave periods to manually shut down the pipelines if electronic systems fail; and steps to prevent leaks at other places where Line 5 crosses waterways.

The agreement also includes a process for dealing with the existing oil lines after they're deactivated, although it leaves open the question of how much of the pipe material will be removed.