WASHINGTON (AP) — Chevron was nearly booted from Venezuela in 2007 during a nationalization drive led by the late socialist President Hugo Chavez. Twelve years later, it faces a similar threat from an unlikely corner: the White House.

The Trump administration is facing a July 27 deadline to renew a license granting Chevron permission to continue operating in Venezuela despite U.S. sanctions aimed at ousting President Nicolás Maduro by choking off revenue from the world's largest crude reserves.

Chevron has operated in the South American country for almost a century and its four joint ventures with state-run oil monopoly PDVSA currently produce about 200,000 barrels a day. That's about a quarter of Venezuela's total production in June, according to the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries.

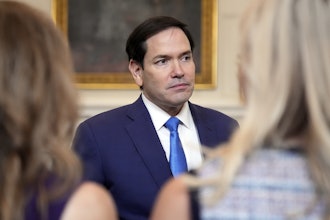

For Trump, it's a dilemma. The billionaire president prides himself on being a booster of Big Oil. But he's also taken several bold steps to oust Maduro, including imposing harsh oil sanctions, threatening military action and recognizing opposition leader Juan Guaidó as Venezuela's rightful leader.

So far, the Trump administration hasn't signaled which way it will go and its National Security Council declined to comment.

But if Chevron is forced to leave, the country's oil production, which has already plunged to its lowest level in seven decades, is likely to spiral even further downward.

"It's doubtful PDVSA would be able to sustain production at current levels given its severe financial problems," said Justin Jacobs, an oil analyst at IHS Markit.

Foreign policy analysts fear that in removing the last major American outpost in Venezuela, oil fields Chevron helps operate would wind up in the hands of U.S. adversaries like Russia or China, both of which are staunch allies of Maduro.

When the U.S. Department of Treasury sanctioned PDVSA in January in support of Guaidó, it granted waivers to Chevron and four oil service companies —Hallburton, Schlumberger, Weatherford and Baker Hughes.

Since then, the San Ramon, California-based company has been seeking to get the license extended, according to two people familiar with the company's actions who spoke on the condition of anonymity because they weren't authorized to discuss the matter. One of the sources said the company recently looked at renting homes for its managers in the coastal city of Puerto La Cruz, near its operations in the heavy crude Orinoco Belt, a sign that it isn't planning to leave anytime soon. This year, Chevron has spent $2.8 million on lobbying U.S. agencies on a variety of issues, including Venezuela, according to company filings.

Chevron wouldn't say whether it wants to continue operating in Venezuela, but said it complies with all applicable laws and regulations. "As everywhere else, we take a long-term approach in our investment. We continue to stay focused on our base business operations," said spokesman Ray Fohr.

In its long run in Venezuela, Chevron has weathered bouts of turmoil before. In 2007, as rivals Exxon and Conoco fled the country and sued amid a nationalization drive, Chevron rode alone in taking up Chavez's offer to form a joint venture with PDVSA on what were widely seen as unfavorable terms.

Thus began a close — some say overly so — relationship with Venezuela's frequently anti-American government led by Ali Moshiri, then Chevron's top executive for Latin America and who Chavez once called a "comrade" and "dear friend." Over the next few years, Chevron would form a number of joint ventures that helped generate badly needed cash for Chavez and then Maduro at a time the economy was falling apart.

In 2017, Moshiri, who was then retired, and a Chevron executive traveled to Caracas to meet with Maduro a few days after the Trump administration banned U.S. banks from lending money to Venezuela's government or PDVSA. Chevron drew heat for the meeting after the government released a photo showing the two men sitting down with Maduro and Vice President Vice President Tareck El Aissami, who the U.S. had sanctioned months earlier as a drug kingpin.

Fohr, Chevron's spokesman, said those meetings "comply with all applicable laws and regulations, including the U.S. sanctions directed toward Venezuela."

The warm ties entailed huge risks. Federal prosecutors in Florida and Texas have been conducting a sweeping investigation into fraud at PDVSA that has already resulted in charges against 33 individuals, including former PDVSA employees, and 20 guilty pleas. Last year, two local Chevron executives were arrested by Venezuelan security forces and held for nearly two months amid an anti-corruption purge in the oil industry.

Fohr said the two employees were released on June 6, 2018, after a favorable court ruling because "Chevron did not violate any Venezuelan law."

That incredible resilience is now one of the main arguments for allowing the company to stay.

Chevron is the last major American footprint in Venezuela after several other companies — Colgate, General Motors, the Kellogg Co. — have shut down in recent years, unable to cope with widespread shortages and hyperinflation that topped 130,000% last year. With the Trump administration's decision to close its embassy in Caracas in March, the sort of on-the-ground political insight and contacts Chevron can provide, especially about the critical oil sector, is harder than ever to come by. Should the U.S. succeed in removing Maduro, the company could also play a key role rebuilding the economy.

While the four joint ventures with PDVSA currently produce about 200,000 barrels a day in total, Chevron's net daily production at the company's joint ventures averaged 42,000 barrels of crude oil in 2018.

But some want Trump to go for the jugular. While for Chevron, the world's seventh largest oil producer by revenue, its production in Venezuela is a drop in the bucket, for Maduro it's a valuable lifeline.

Carlos Vecchio, Guaido's diplomatic envoy to the White House, told The Associated Press that the fate of Chevron in Venezuela "is a decision that only the U.S. government can discuss and decide." He refused to say which option is favored by Guaidó.

But even some hardliners question how effecting kicking out Chevron would be. Pedro Burelli, a U.S.-based consultant who was a PDVSA executive board member until 1998, said the decision about the waiver on its own is irrelevant because the Trump administration has been unable to effectively coordinate sanctions with other policies to force Maduro out.

"They need to finish off the job and kicking out Chevron alone won't generate a total collapse" of Maduro's government, Burelli said.

Meanwhile some complain Chevron is getting favorable treatment.

Earlier this year, just before sanctions were imposed, a little-known U.S. energy firm partly owned by Florida Republican donor Harry Sargeant III inked a deal with PDVSA to invest up to $500 million to revitalize three oil fields.

Sargeant, who met with Maduro as he negotiated the deal, said that while he complies with the U.S. decisions he believes unilateral sanctions are rarely effective in producing regime change. He insists that what he calls an "America Last" policy will likely open space for less scrupulous Russian and Chinese companies that will harm U.S. interests in the region as well as the Venezuelan people.

"The Russians, in particular, may seek a strategy of producing enough oil to help maintain the regime but not enough to depress artificially-high oil prices or stem the humanitarian crisis," Sargeant told the AP.

"The US government should not be in the business of playing favorites," he added. "Waivers or licenses should either be granted to all American companies or should be withheld from all American companies."