High-tech manufacturers around the world are currently looking at a historic window of opportunity for growth. Data centers continue to expand, telecom companies are rolling out 5G, demand for consumer electronics remains strong despite inflationary pressure, and remote work seems to be here to stay. Many high-tech companies could generate 50 to 100% revenue growth over the next five years if they are able to respond effectively.

Yet, the challenges currently facing their supply chains are well known—from stockouts, excess inventory, and supply shortages to global constraints on delivery capacity and logistics, geopolitical and trade tensions, industrial accidents, and natural disasters. All of these severely threaten companies’ ability to meet demand. Lead times for many components have expanded from pre-pandemic averages of 12 to 14 weeks to more than 40 weeks. Some high-tech facilities have seen their production disrupted or even closed. More recently, ongoing Russia–Ukraine hostilities threaten to jeopardize key inputs, such as natural gases, that are critical to semiconductor manufacturing.

Responding to these challenges has been difficult, given that few manufacturers have sufficient transparency into their supply chains to understand where demand is headed in real time and the ability to pivot quickly enough to adjust supply to meet that demand. Instead, they tend to address problems as they arise, often misunderstanding the underlying causes or failing to note the presence of several interrelated issues.

Why is it So Hard to Know What’s Going On?

Across high-tech manufacturing today, semiconductor shortages have triggered order backlogs throughout an industry in which IT and data-management systems are often too inflexible to adapt. Meanwhile, customers looking for firm delivery commitments are banging down the door.

For example, one leading high-tech manufacturer with a global footprint found its customers continually demanding to know when their orders would arrive. Although the business had clear growth potential reflected in accelerating demand for its products, its cumbersome data processes meant that the company struggled to develop realistic commitments about what products it could deliver and when. By the time the deadline for firm commitments came and went, supply conditions had often changed and many particular promises were no longer feasible.

In a distinctly un-capitalistic turn, not even the highest bidders were rewarded: even when some customers offered substantial premiums to get products they needed within a certain time frame, the company was unable to peg the necessary components for those products to individual customers—no matter how much they were willing to pay. It simply lacked the visibility into where each of its dozens of product components was located in the world, how many it had on hand, or how those numbers might change.

This scenario betrays the underlying issue that most companies rely on data generated by disparate systems, with insights from that data siloed across functions. The outcome is hundreds of Excel spreadsheets emailed to suppliers, contract manufacturers, and customers containing information that is often outdated within a week. These manual processes also mean that companies are slow to react to changes in component availability or demand for a given product. In today’s environment, situations of this nature hand growth opportunities to the most agile competitor.

Sense and Pivot to Stay Competitive

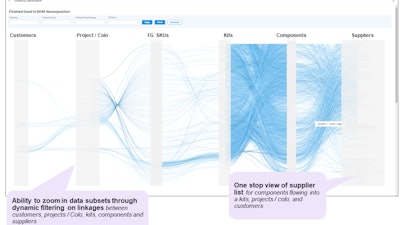

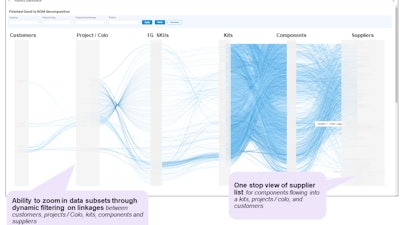

Agility is king—for high tech companies and indeed across many other industries. The manufacturer in our example knew it needed to move quickly to gain visibility into and control of its supply chain. In response, it set about creating an analytical model that could aggregate and connect its many disparate sets of data. This model gave the business real-time visibility into the availability of components across customers, product families, manufacturing sites, and product SKUs (see figure below.) The model also visually represented to the business where its key decisions needed to be made, while allowing it to base those decisions on all of the relevant data flowing through its systems—rather than distilling hundreds of manually developed spreadsheets.

The above chart shows how a unified, integrated view of product flow makes it possible to accurately peg components to finished goods demand and customers

The above chart shows how a unified, integrated view of product flow makes it possible to accurately peg components to finished goods demand and customers

Having this model allowed the company to translate its data about component availability into the exact number of products the business would be able to deliver to customers in a given week or month. Even more important, it also allowed the company to optimize the allocation of those components to a given product or customer based on any chosen financial metric, such as revenue or profits. In this way, the company could prioritize the customers who had offered to pay more; alternatively, it could allocate scarce components to the most profitable items in its product portfolio.

Today, the manufacturer in our example uses its newfound abilities to solve problems before they arise. By monitoring internal and external demand and supply, it can foresee disruptions and potential risks to the supply chain. In addition, the business has adapted its processes to support faster, data-driven decision making throughout the commercial, procurement, manufacturing, and fulfillment stages—allowing it to adapt quickly to meet demand or reduce its commitments when necessary.

This company’s approach—and their success in implementing the model—is a best-in-class example of a “sense and pivot” framework that centers on gaining visibility, stability, and control over all aspects of a supply chain. The real-world applicability and effectiveness of this framework has never been stronger. Using the appropriate technology, companies of all sizes can employ it to sense potential risks to their supply chains and pivot rapidly to mitigate those risks.

---

About the Authors

P.S. Subramaniam and Hieu Pham are partners in the Operations and Performance practice of global strategy and management consultancy Kearney. They can be reached, respectively, at [email protected] and [email protected]. The authors would like to thank Archit Johar and Dylan Lee for their contributions to this article.

They can be reached, respectively, at [email protected] and [email protected]. Authors would like to thank Archit Johar and Dylan Lee for their contributions to this article.