Floating fences in India. Whimsical water- and solar-driven conveyor belts with googly eyes in Baltimore. Rechargeable aquatic drones and a bubble barrier in The Netherlands.

These are some of the sophisticated and at times low-tech inventions being deployed to capture plastic trash in rivers and streams before it can pollute the world's oceans.

The devices are fledgling attempts to dent an estimated 8.8 million tons (8 metric tons) of plastic that gets into the ocean every year. Once there, it maims or kills marine plants and animals including whales, dolphins, and seabirds and accumulates in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch and other vast swirls of currents.

Trash-gobbling traps on rivers and other waterways won’t eliminate ocean plastic but can help reduce it, say officials with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Marine Debris Program.

“It’s just hard to get out to our big open oceans and collect the trash there," said Director Nancy Wallace. “We’d much rather collect that trash closer to shore, which is easier. It's less costly, and we can have that impact before it gets into the ocean.”

Trash is blown, washed or thrown into waterways nearly everywhere. Storm drains funnel in litter tossed onto streets. In places without refuse collection, people use convenient waters to carry trash away.

The science of plastic pollution is new and almost as much in flux as the waters it studies. For instance, a scientist who reported in 2017 that rivers might carry anywhere from 450,000 to 4.4 million tons (410,000 to 4 million metric tons) of plastic a year into the sea also was part of a 2021 study that narrowed the range considerably, with an upper limit of nearly 3 million tons (2.7 million metric tons).

“Compared to other pollutants ... available data on plastics is still scarce,” Christian Schmidt, of the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research in Leipzig, Germany, wrote in an email.

D.C. Sekhar of Bengaluru, India, designed a low-tech trap for rivers in his country after he left a career in commercial shipping.

As an oil tanker captain, “I had traveled around the world and seen waterbodies that were fairly clean,” while trash fouled India’s, he said.

Wanting something modular, inexpensive, easy to maintain and able to withstand monsoons, he designed stainless steel mesh fences that extend above and below aluminum floats 3.9 feet (1.2 meters) long.

Sekhar's AlphaMERS Ltd. has installed big floating barriers across rivers at eight southern cities from Hyderabad to Tuticorin. Each is angled to guide trash to a riverbank where excavators pile it into dump trucks.

In this July 2018 photo provided by AlphaMERS Ltd, a floating fence collects trash in the Cooum River in Chennai, India. Many novel devices are being used or tested worldwide to trap plastic trash in rivers and smaller streams before it can get into the ocean.AlphaMERS Ltd via AP

In this July 2018 photo provided by AlphaMERS Ltd, a floating fence collects trash in the Cooum River in Chennai, India. Many novel devices are being used or tested worldwide to trap plastic trash in rivers and smaller streams before it can get into the ocean.AlphaMERS Ltd via AP

Eight traps on India’s Cooum River at Chennai, costing about $120,000 total, corralled about 2,400 tons (2,200 metric tons) of plastics and 21,800 tons (19,800 metric tons) of other trash and floating plants in 2018, their first year in position, said Sekhar.

The system with the biggest fan base may be the anthropomorphized Trash Wheels at the mouths of four Baltimore watersheds.

“We’ve got 100,000 followers across major social media platforms,” said Adam Lindquist, vice president of programs and environmental initiatives for the Waterfront Partnership of Baltimore, which owns three devices.

“They are a really great model for how to get the public involved and attentive to the issue,” MaryLee Haughwout, then acting director of NOAA's Marine Debris Program, said in April. The program has helped pay for trash traps in the Anacostia River outside Washington, D.C., and the Tijuana River estuary in California and Mexico but is not involved with the Trash Wheels.

Lindquist said Mr. Trash Wheel has inspired fans to begin recycling or join trash cleanups, and its trash collection data helped convince the Baltimore City Council to ban foam food containers, effective October 2019.

The number of foam clamshells and cups collected by Mr. Trash Wheel has plummeted from an average of more than 147,000 a year from 2015 through 2018 to 26,760 in 2021, according to data on the website.

The devices use ancient and modern technology to run rakes and a conveyor belt that move floating trash into barge-mounted dumpsters. Usually, the current carrying bottles and cigarette butts also turns a water wheel for power. When the current slows, a solar-powered water pump spins the wheel.

Together, Mr. Trash Wheel, Professor Trash Wheel, Captain Trash Wheel and Gwynnda the Good Wheel of the West, named for Gwynns Falls, have taken in more than 2,000 tons (1,800 metric tons) of trash, including 12.6 million cigarette butts and nearly 1.5 million plastic bottles. They are turned on only during and after rainstorms, when large amounts of trash show up.

Mr. Trash Wheel and his younger “relatives” have curved sailcloth shells above their workings, a water wheel on one side, and sport 5-foot (1.5-meter) googly eyes. Each has a personality profile on the web, and Mr. Trash Wheel has an active Twitter account.

A similar device called Wanda Díaz is being installed on the Juan Díaz River at Panama City, Panama by nonprofit La Marea Verde. It won't have googly eyes but will have AI software to analyze the trash on its conveyor belts.

Larger, entirely solar-powered conveyor belts have been designed for Ocean Cleanup founder Boyan Slat, who is now testing those $775,600 “Interceptors” for river trash.

In The Netherlands, Bubble Barrier Amsterdam pumps compressed air through a perforated tube set across the River IJ at Westerdok, where several canals flow into the river. The tube is set diagonally to direct trash to a rectangular collecting device near the shore.

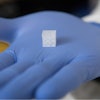

The WasteShark, a boxy 5 foot, 2 inch long (157 centimeter) aquatic drone, was developed about 35 miles (57 kilometers) away in Rotterdam. A drone's hold can accommodate 42 gallons (160 liters) of trash, floating plants and algae, according to RanMarine Technology. They can operate up to eight hours on a charge.

More than 40 have been sold worldwide to buyers in a dozen countries including the U.K, U.S., Nigeria and Singapore, chief operating officer Esther Lokhorst said in an email. Prices start at 23,500 euros (about $25,600) for manually controlled models, more for programmable versions.

Osprey Initiative LLC, of Mobile, Alabama, works on an even smaller scale, setting up floating traps on creeks, canals and rivers in the U.S. Southeast and training local crews to empty the traps, then sort, analyze and dispose of trash.

An employee of Osprey Initiative lays boom as the company installs a trap called a Litter Gitter to help collect trash floating in a canal before it can travel into larger bodies of water in Metairie, La., Thursday, May 19, 2022. Many novel devices are being used or tested worldwide to trap plastic trash in rivers and smaller streams before it can get into the ocean.AP Photo/Gerald Herbert

An employee of Osprey Initiative lays boom as the company installs a trap called a Litter Gitter to help collect trash floating in a canal before it can travel into larger bodies of water in Metairie, La., Thursday, May 19, 2022. Many novel devices are being used or tested worldwide to trap plastic trash in rivers and smaller streams before it can get into the ocean.AP Photo/Gerald Herbert

The company employs about eight to 10 people full-time, with about 30 part-time local workers at projects across nine states, said owner and founder Don Bates. “If you can work with us part time for six months -- and our work is dirty, nasty work -- you come out of it with a changed view of your impact on the environment,” he said.

In the end, said NOAA’s Haughwout, reducing marine plastic will require fundamental changes such as making and using less, particularly single-use plastics such as straws or cutlery; recycling; reusing what you can and choosing reusable items over disposable ones.

“In addition to disposing of waste I like to emphasize awareness,” she said. “I think people don't understand how they contribute.”