UCLA engineers have designed a thin adhesive film that could upgrade a consumer smartwatch into a powerful health-monitoring system. The system looks for chemical indicators found in sweat to give a real-time snapshot of what's happening inside the body.

A study detailing the technology was published in the journal of Science Advances.

Smartwatches can already help keep track of how far you've walked, how much you've slept and your heart rate. Newer models even promise to monitor blood pressure. Working with a tethered smartphone or other devices, someone can use a smartwatch to keep track of those health indicators over a long period of time.

What these watches can't do, yet, is monitor your body chemistry. For that, they need to track biomarker molecules found in body fluids that are highly specific indicators of our health, such as glucose and lactate, which tell how well your body's metabolism is working.

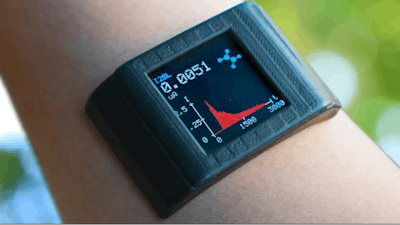

To address that need, the researchers engineered a disposable, double-sided film that attaches to the underside of a smartwatch. The film can detect molecules such as metabolites and certain nutrients that are present in body sweat in very tiny amounts. They also built a custom smartwatch and an accompanying app to record data.

"The inspiration for this work came from recognizing that we already have more than 100 million smartwatches and other wearable tech sold worldwide that have powerful data-collection, computation and transmission capabilities," said study leader Sam Emaminejad, an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering at the UCLA Samueli School of Engineering. "Now we have come up with a solution to upgrade these wearables into health-monitoring platforms, enabling them to measure molecular-level information so that they give us a much deeper understanding of what's happening inside our body in real time."

The skin-touching side of the adhesive film collects and analyzes the chemical makeup of droplets of sweat. The watch-facing side turns those chemical signals into electrical ones that can be read, processed and then displayed on the smartwatch.

The co-lead authors on the paper are graduate student Yichao Zhao and postdoctoral scholar Bo Wang. Both are members of Emaminejad's Interconnected and Integrated Bioelectronics Lab at UCLA.

"By making our sensors on a double-sided adhesive and vertically conductive film, we eliminated the need for the external connectors," Zhao said. "In this way, not only have we made it easier to integrate sensors with consumer electronics, but we've also eliminated the effect of a user's motion that can interfere with the chemical data collection."

"By incorporating appropriate enzymatic-sensing layers in the film, we specifically targeted glucose and lactate, which indicate body metabolism levels, and nutrients such as choline," Wang said.

While the team designed a custom smartwatch and app to work with the system, Wang said the concept could someday be applied to popular models of smartwatches.

The researchers tested the film on someone who was sedentary, someone doing office work and people engaged in vigorous activity, such as boxing, and found the system was effective in a wide variety of scenarios. They also noted that the stickiness of the film was sufficient for it to stay on the skin and on the watch without the need for a wrist strap for an entire day.

Over the past few years, Emaminejad has led research on using wearable technology to detect indicator molecules through sweat. This latest study shows a new way that such technologies could be widely adopted.

"We are particularly excited about our technology because by transforming our smartwatches and wearable tech into biomonitoring platforms, we could capture multidimensional, longitudinal and physiologically relevant datasets at an unprecedented scale, basically across hundreds of millions of people," Emaminejad said. "This thin sensing film that works with a watch shows such a path forward."