PHOENIX (AP) — A man associated with Arizona State University who was one of the first people in the United States to test positive for the then-new coronavirus in January does not appear to have spread it to anyone else, researchers report.

But the virus was able to take root weeks later. In late February or early March, someone arrived in Arizona with the virus and it spread, setting off a chain of infections that transmitted clandestinely before they were identified.

Those are some of the initial findings from an extensive data analysis process announced this week by researchers from the Phoenix-based Translational Genomics Research Institute, Northern Arizona University and the University of Arizona.

Using supercomputers to analyze genomes of virus samples taken in Arizona, researchers are now tracing the outbreak to understand where the virus is coming from, how it's spreading through the population and whether it's mutating in ways that would make existing tests or future vaccines unreliable.

“We know the virus didn’t come into Arizona and roll across like a tidal wave,” said David Engelthaler, one of the lead scientists working on the project. “It’s coming in in spurts and starts from different places, and we can track what states or countries they’re coming from.”

Engelthaler, formerly Arizona's top epidemiologist, is an associate professor of the Pathogen and Microbiome Institute at TGen and Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff.

He created the Arizona COVID-19 Genomics Union with fellow university and TGen professor Paul Keim and University of Arizona professor Michael Worobey.

Engelthaler and colleagues are mapping the virus like a family tree. Some branches are short, like the one from the person from Arizona State University, who had been in Wuhan, China, where the virus originated, before getting sick and isolating at home in the Phoenix area. Other virus branches keep growing as people get infected and go on to infect others.

The virus mapping can allow public health officials to understand how the disease is spreading — and to better target efforts to contain it.

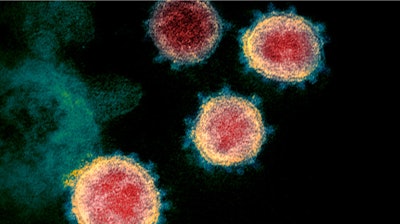

For most people, the coronavirus causes mild or moderate symptoms, such as fever and cough that clear up in two to three weeks. For some, especially older adults and people with existing health problems, it can cause more severe illness, including pneumonia and death. The vast majority of people recover.

Researchers said the strain that took root in early March circulated in Europe before getting a foothold in Arizona. It's unclear if the traveler who brought it to Arizona became infected overseas or in one of the other U.S. states where the same strain has been found, including Washington and Utah.

While the spread of the virus through that person accounts for more infections than other strains circulating in Arizona, it's still less than half of the tested samples, the researchers said.

Researchers don't know who the traveler is or precisely when he or she arrived in Arizona. On March 10, there were only six confirmed infections in Arizona, nobody had died and the state had not yet closed schools and restaurants or ordered people to stay home.

“Before we took really extensive measures statewide, this virus was already established and transmitting,” said Worobey, who researches pandemics as head of the University of Arizona's Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology.

The various strains have enough genetic differences that researchers can tell them apart and trace their spread around the world, but they all seem to behave the same in humans, the researchers said. There's no indication that some variants are more virulent than others, they said.

Researchers have mapped about 100 genomes in Arizona and expect to hit 200 by the end of the week, with capacity to map hundreds per week going forward.

Keim expects the outbreak to result in enduring behavioral changes including better hygiene, less handshaking and a greater level of social acceptance for people who stay home from work when sick.

“We’re not ever going to go back to normal, in my opinion,” Keim said. “At least not this generation, the people who have lived through this.”