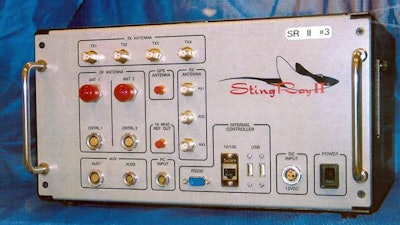

NEW YORK (AP) — Michael Cohen, meet the Triggerfish.

Search warrant documents made public Tuesday show the FBI used highly secretive and controversial cellphone sweeping technology to zero-in on President Donald Trump's former personal lawyer when agents raided his New York City home, hotel room and office last year.

Agents using a Triggerfish cell-site simulator tracked the whereabouts of Cohen's two iPhones to a pair of rooms a floor apart at the Manhattan hotel where he and his family had taken up residence while their apartment was being renovated, according to the documents.

The FBI said in its April 8, 2018 warrant application that it was only using the device to locate Cohen's phones, not to intercept his calls or text messages. The raid happened the next day.

Separately, the agency obtained logs of the numbers Cohen was calling and texting, and reams of location data — including for the time period just before the 2016 presidential election, when he negotiated hush-money payments for women alleging they had sex with Trump. They also got permission to press Cohen's thumb to the phones or hold them up to his face to unlock them.

But it was the agency's use of cell-site technology that stood out amid nearly 900 pages of documents from the Cohen raids.

Civil liberties and privacy groups have been objecting to the suitcase-sized devices, sometimes known as StingRays or Hailstorms, which act like a cell tower and often connect to cellphones other than the person being tracked. Police departments and federal agencies have been using them in relative secrecy for nearly three decades. The earliest references online date to 1991.

The technology, originally developed for the military, can pull data from a target's devices — but also from unwitting people whose phones connect to the phony cell tower because it's often closest and shows the strongest signal. Police can determine the location of a phone without the user even making a call or sending a text message. Some even allow law enforcement to listen in on conversations or see text messages as they're being sent and received.

"They're very dangerous devices in that they intercept all cellular communications in the area," said Adam Scott Wandt, a lawyer and professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City.

The government said it did not want Cohen notified of its high-tech efforts to track his communications because it had reason to believe that would lead to evidence tampering or destruction, witness intimidation or other actions that would "seriously jeopardize an ongoing investigation."

In New York, use of the technology was virtually unknown to the public until the New York Civil Liberties Union forced the disclosure of records showing the NYPD used the devices more than 1,000 times since 2008. The organization is pushing a bill that would require the department to regularly disclose information about its use of the devices.

That included cases in which the technology helped catch suspects in kidnappings, rapes, robberies, assaults and murders. It has even helped find missing people. But defense lawyers have also fought to limit the use of evidence collected with the devices.

"Any time law enforcement gets to operate in complete secrecy and there's little to no oversight and with no ability for defense attorneys to challenge it in a court of law, you run into significant problems," said Legal Aid lawyer Jerome Greco.