TOKYO (AP) — Japan partially lifted an evacuation order in one of the two hometowns of the tsunami-wrecked Fukushima nuclear plant on Wednesday for the first time since the 2011 disaster.

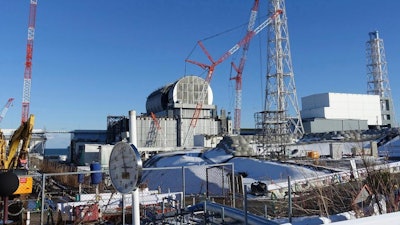

Decontamination efforts have lowered radiation levels significantly in the area about 7 kilometers (4 miles) southwest of the plant where three reactors had meltdowns due to the damage caused by the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami.

The action allows people to return to about 40 percent of Okuma. The other hometown, Futaba, remains off-limits, as are several other towns nearby.

Many former residents are reluctant to return as the complicated process to safely decommission the plant continues. Opponents of lifting the evacuation orders in long-abandoned communities say the government is promoting residents' return to showcase safety ahead of the Tokyo Olympics next summer.

The government has pushed for an aggressive decontamination program by removing topsoil, chopping trees and washing down houses and roads in contaminated areas, though experts say the effort only caused the contamination to move from one place to another, creating massive amounts of radioactive waste and the need for its long-term storage.

The meltdowns at three of Fukushima Dai-ichi's six reactors caused massive radiation leaks that contaminated the plant's surroundings, forcing at its peak some 160,000 people to evacuate their homes for areas elsewhere in Fukushima or outside the prefecture.

Evacuation orders in most of the initial no-go zones have been lifted, but restrictions are still in place in several towns closest to the plant and to its northwest, which were contaminated by radioactive plumes from the plant soon after its meltdowns. More than 40,000 people were still unable to return home as of March, including Okuma's population of 10,000.

Town officials say the lifting of the evacuation order in the two districts would encourage the area's recovery.

"We are finally standing on a starting line of reconstruction," Okuma mayor Toshitsuna Watanabe told reporters.

A new town hall is opening in the Ogawara district in May and 50 new houses and a convenience store is underway. But the town center near a main train station remains closed due to radiation levels still exceeding the annual exposure limit and a hospital won't be available for two more years, requiring returnees to drive or take a bus to a neighboring town in case of medical needs.

Anti-nuclear sentiment and concerns about radiation exposures remain high in Japan since the disaster, leaving many people skeptical about the safety declaration by the government and utility operators, as risks of developing cancer and other illnesses from low-dose, long-term radiation exposures are still unknown. Critics also say that the annual exposure limit of 20 millisievert, the same as nuclear workers and up from 1 millisievert before the Fukushima meltdowns, is too high.

Many people are reluctant to return home because of lingering concerns about radiation, and they have adapted to new jobs and homes after more than eight years away.

Only 367 people, or less than 4 percent of Okuma's population, registered as residents in the two districts where the order was lifted. A survey last year found only 12.5 percent of former residents wanted to return to their hometown. The government hopes to allow some of Futaba's 5,980 residents to return next year.

Okuma is also home to a temporary storage facility for the radioactive waste that came out of the decontamination efforts across Fukushima. A much delayed facility is still underway.

Fukushima plant's operator, Tokyo Electric Power Co., and government officials plan to start removing the melted fuel in 2021 from one of the three melted reactors, but still know little about its condition inside and have not finalized waste management plans.