WASHINGTON (AP) — The U.S. economy has delivered steady if only modest gains for most Americans since the Great Recession ended in 2009. It's been a frustration for many.

Yet the very sluggishness of the economic expansion helps explain why it's now the second-longest on record and why more of the country might soon benefit from higher pay.

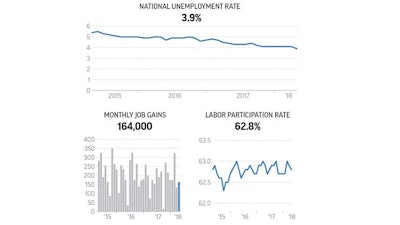

Nearly nine years into the recovery, the job market keeps delivering: The government said Friday that employers added 164,000 jobs in April — the 91st straight month of hiring growth, the longest such streak on record. More tellingly, the unemployment rate fell to 3.9 percent, the lowest since December 2000. Eight years ago, the jobless rate was 10 percent.

But for much of the expansion, many people have felt left behind. Some have found only part-time work. Pay growth, on average, has been meager. The stock market boom and low interest rates that defined the recovery have favored the wealthy.

The economy's modest growth, though, has helped prevent it from overheating and skidding into another recession, as often happened during more robust expansions. And some economists say the ever-lower unemployment rate suggests that a wider swath of Americans soon stand to benefit from stronger pay growth.

"It's just not sustainable for average pay growth to be so low in a labor market this tight," said Andrew Chamberlain, chief economist at the jobs site Glassdoor.

Average hourly earnings have risen 2.6 percent from a year ago. That is slightly more than the year-over-year wage growth of roughly 2 percent that prevailed in 2014 and 2015, when the unemployment rate was higher. Yet by historical standards, wage growth has been relatively stagnant.

Past expansions have delivered faster growth. But since World War II, they have lasted an average of less than five years before slipping into recession.

Gus Faucher, chief economist for PNC Financial, said he thinks annual wage growth could average 3 percent by the end of the year. He notes that employers are having an increasingly difficult time finding qualified workers, creating pressure for them to raise wages.

That may explain why the pace of job growth was slower in March and April: There aren't enough unemployed people to fill openings.

Knutec, a company in Bradenton, Florida, that builds communication network systems, hopes to double its 19-person staff in the next 60 days to meet demand from customers.

Troy Knutson, a founder of the company, said he offers $15 an hour to new employees, who are usually trained on the job how to haul cable and install networks. He said he's now competing against fast food restaurants that are offering workers roughly the same starting wage. The difference, Knutson says, is that his company will provide a career path, cover the costs of health insurance and generally raise a worker's pay to $35 an hour after five years.

"The job market is getting competitive, and people are able to request higher wages," he said.

An encouraging sign for the economy is that the pace of hiring has yet to be disrupted by dramatic global market swings, a recent pickup in inflation or the risk that the tariffs being pushed by President Donald Trump could provoke a trade war.

Much of the economy's durability is due, in fact, to the healthy job market. The increase in people earning paychecks has bolstered demand for housing, even though fewer properties are being listed for sale. Consumer confidence has improved over the past year. And more people are shopping, with retail sales having picked up in March after three monthly declines.

Manufacturers added 24,000 workers last month, a sign that possible tariffs on steel, aluminum and Chinese goods haven't altered hiring plans at most U.S. factories. Restaurants and hotels hired a net 18,000. The health care and social assistance sector added 29,300 jobs and the construction industry 17,000.

With qualified job applicants harder to find in many industries, employers have become less and less likely to shed employees. The four-week moving average for people applying for first-time unemployment benefits has reached its lowest level since 1973.

The trend reflects a decline in mass layoffs. Many companies expect the economy to keep expanding, especially after a dose of stimulus from tax cuts signed into law by Trump that have also increased the federal budget deficit.

Inflation has shown signs of accelerating slightly, eroding some of the potential wage growth. Consumer prices rose at a year-over-year pace of 2.4 percent in March, the sharpest annual increase in 12 months.

The Federal Reserve has set an annual inflation target of 2 percent. Investors expect the Fed to raise rates at least twice more this year, after an earlier rate hike in March, to keep inflation from climbing too far above that target. Many economists saw the April jobs report as confirming that forecast.

Scott Anderson, chief economist at the Bank of the West, said the April jobs report suggests that inflation may remain tame, which means the Fed might not raise rates more than three times this year.

"Slower job growth with little sign of inflation pressures is just what the doctor ordered to keep this economic expansion on track without a serious case of overheating," Anderson said.