PORTLAND, Maine (AP) — The seafood industry has been upended by the spread of the coronavirus, which has halted sales in restaurants and sent fishermen and dealers scrambling for new markets.

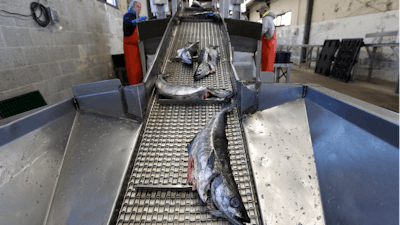

Seafood is a global industry that relies on a complex network of fishermen, processors, buyers and distributors, all of which have been affected by the virus. A lack of demand has sent prices tumbling and led some fishermen to tie up their boats until the outbreak subsides.

Members of the U.S. seafood industry are calling on the Trump administration and Congress to help them weather the uncertain time. But for now, the market for big-money items such as scallops and lobster is “pretty much nonexistent,” said Bert Jongerden, general manager of the Portland Fish Exchange, a Maine auction house.

The auction house usually moves up to 60,000 pounds (27,215 kilograms) of fish in a week but is down to less than a third of that, Jongerden said.

“Heard some stories with people coming in with lobsters saying dealers wouldn’t take them,” Jongerden said. “And we don’t have a lot of fish.”

Shelter-in-place rules and closures have kept customers out of restaurants, where seafood typically fetches high prices. The worldwide shipping industry has also slowed considerably, in part because major markets like China, Italy and Spain have been hit especially hard.

The result has been plummeting wholesale prices. The wholesale price for live 1.25-pound (570-gram) lobsters in March was 33% under 2018 levels, according to business publisher Urner Barry. A ripple effect has been a slowdown in distribution, processing and the most important piece of the supply chain — fishing.

The industry could further suffer from economic slowdown, said industry analyst John Sackton, publisher of SeafoodNews.com. Customers worried about a recession might be wary of spending their grocery budgets on seafood, which tends to be more expensive than other proteins, he said.

The turmoil has prompted industry associations and companies with a stake in seafood, ranging from commodity giants like Cargill to local businesses, to ask the federal government for assistance. A coalition of organizations, including the National Fisheries Institute and National Aquaculture Association, sent a letter to the Trump administration in late March.

The coalition suggested the federal government appropriate $500 million to purchase surplus commercial seafood that can be shipped overseas or supplied to domestic organizations.

“Failure to act boldly now to preserve our country’s seafood infrastructure will impose far greater costs on our economy and cause permanent damage to our nation’s ability to harvest, farm, process, and distribute seafood products,” the coalition wrote.

An aid package approved March 27 included $300 million to boost the industry. The stimulus package set aside the money for fishermen, fishing communities, processors and others who have suffered economic harm due to the virus. That could include direct payments.

Some are turning to the retail market to try to help the industry stay afloat. Customers are still buying seafood at supermarkets, and there’s a possibility for growth because more Americans are cooking at home amid shutdowns, Jongerden said.

That could help the industry navigate a difficult time, said Ben Martens, executive director of the Maine Coast Fishermen’s Association, which represents small-boat fishermen in Maine.

“If we can get people playing with seafood at home again, it’s super good for our fishermen, it’s super good for our economy,” he said.

April is key to the New England scallop fishing season, and members are hopeful for better prices — but it’s difficult to gauge what the market will look like, he said.

In Canada, where much of the world’s lobster is processed, they're watching closely to see when the pandemic might abate, said Jerry Amirault, president of the Lobster Processors Association of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Processors normally get started in early May, but fishermen need to catch lobsters first, and this year’s harvest is in question.

“We’re all undergoing the same type of realization — this is an exceptional time in this pandemic,” he said.